Python + Go: The basics

python go C web theory packages

Table of contents

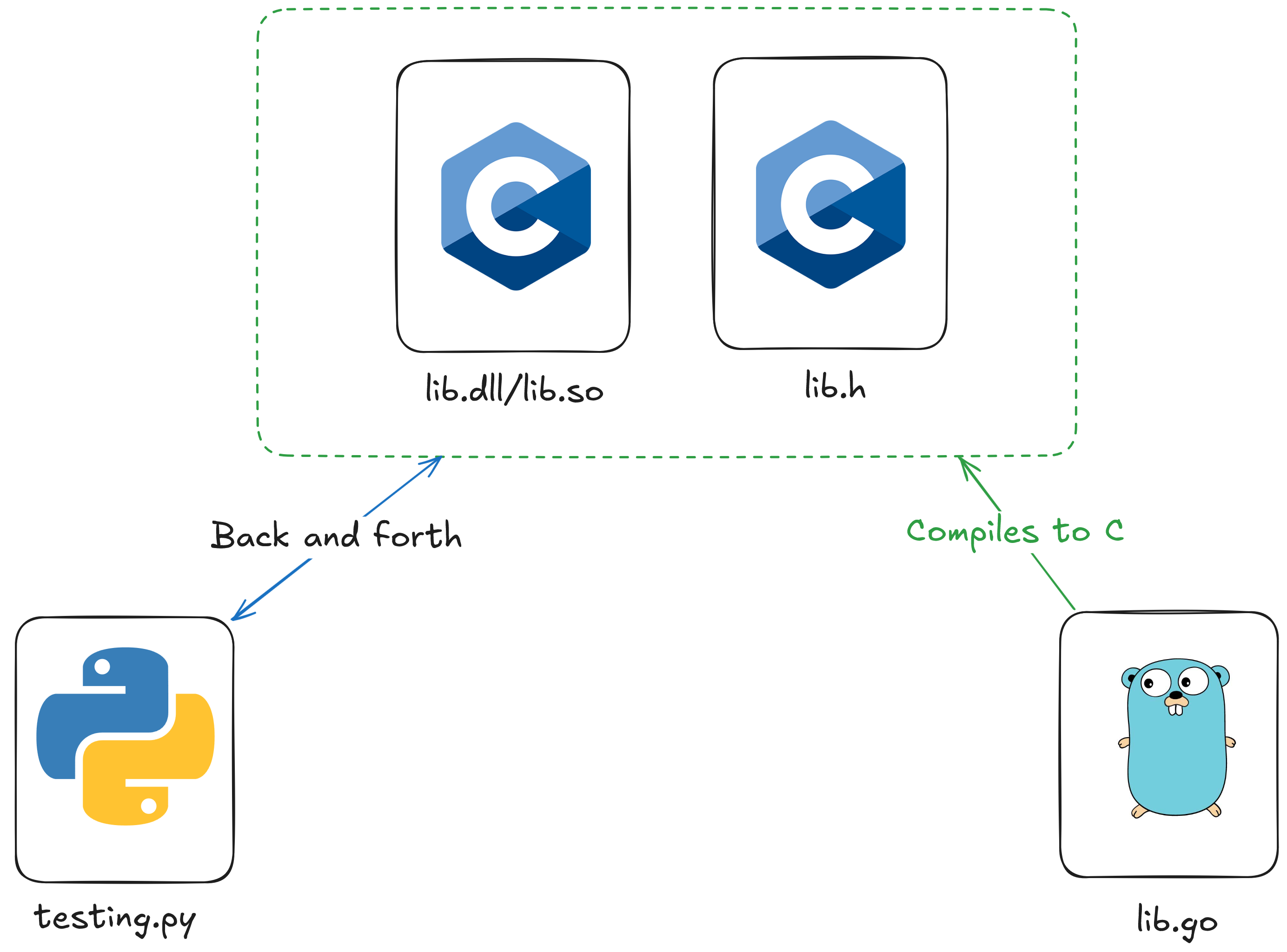

Python can be slow at the best of times, but switching to another language can waste a ton of your time rewritting. Instead, is it worth it to integrate libraries written in other languages for the slow parts of python, and use python for the rest? What are the pros and cons to doing this?

Before starting this article is quite a bit more complicated than my usual ones. I try to make things simple, but to fully understand it you will need to know:

- Python quite well

- Enough go and C to at least be able to read, and conceptually understand the code

- If you want to be able to work with structs/classes and strings you will also need to understand how they work in C

For Go I would recommend:

For C:

If you haven’t seen it yet, I would highly recommend reading the introduction article and then coming back. It’s short, and gives you handy information you need to understand this article.

Easy parts

So, let’s get started with the simple stuff. A function in go that prints something, and calling it from python. First let’s setup the Go code.

Go

To get started run go mod init lib, this will setup our go project in the folder. From there you can create a file called lib.go. As a sanity check let’s try just running our code in go:

lib.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func Greeting() {

fmt.Println("Hello from Go!")

}

func main() {

Greeting()

}Now run go run lib.go, and you should get Hello from Go! in your terminal. Now let’s add one more function called Factorial() that will take in a number, and return the factorial of it:

lib.go

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

func Greeting() {

fmt.Println("Hello from Go!")

}

func Factorial(n int) int {

result := n

lastVal := n - 1

for range int(n) {

if lastVal > 0 {

result *= lastVal

lastVal -= 1

}

}

return result

}

func main() {

Greeting()

fmt.Printf("The factorial of 10 is %d\n", Factorial(10))

}Running go run lib.go again will result in the greeting from before and The factorial of 10 is 3628800. So, now we just need to prepare these functions for python.

Prepping cgo

First we will need to pull in the cgo library, this is done with a separate import statement, and a multiline-comment above (this will be important later):

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

)

// rest of the code hereIf you are getting errors in your editor you will need to setup a proper C compiler. For me I am going to use zig cc. Zig is yet another programming language, but it’s compiler can compile C code, and it works cross platform (handy since I’m on windows and every other gcc didn’t work for me). If you’re on linux/MacOS and have gcc already, and don’t want another thing installed on your system, feel free to skip to converting functions.

To setup zig cc first download zig, once you have it setup you should be able to run the following commands to set it as your CGo compiler:

- Get the binary location, on windows run

where zigand copy the path, on linux/MacOS runwhich zig - Run the command below replacing

$PathToCompilerwith the path you found using the command from step 1 +zig cc. So for me when I typewhere zigI getC:\binaries\zig-windows-x86_64-0.14.0-dev.2613+0bf44c309\zig.exe, so I would replace$PathToCompilerwithC:\binaries\zig-windows-x86_64-0.14.0-dev.2613+0bf44c309\zig.exe cc

Now set zig cc as your compiler using (add "" around $PathToCompiler to avoid issues with spaces):

go env -w CC="$PathToCompiler"Run go env, and you’ll get a long output, but now your CC variable should be updated:

$> go env

# Other output

set CC=C:\binaries\zig-windows-x86_64-0.14.0-dev.2613+0bf44c309\zig.exe cc

# other outputConverting Functions

Now let’s talk about how to make our functions work. For non-variadic functions (functions with no arguments and no return types) this is easy, we don’t need to change anything, except adding an export tag above the function:

//export Greeting

func Greeting() {

fmt.Println("Hello from Go!")

}Notice there’s no space between the // and export, this is incredibly important. If you add a space this will not export. Also the name of the export must match the function name. You can’t call your function MyFunction() then try to export my_function, this wil break.

Now for the harder part, variadic functions (those with arguments and/or return types). Since we are compiling our code to C, we need to have values that are C compatible. My recommendation for this is to:

- Create a wrapper function

- Give the wrapper function C-compatible values for arguments and/or return types

- In the function convert the C values to go values

- Run your Go code with those values

- Convert the results back to C-compatible values

- Return the C-compatible values

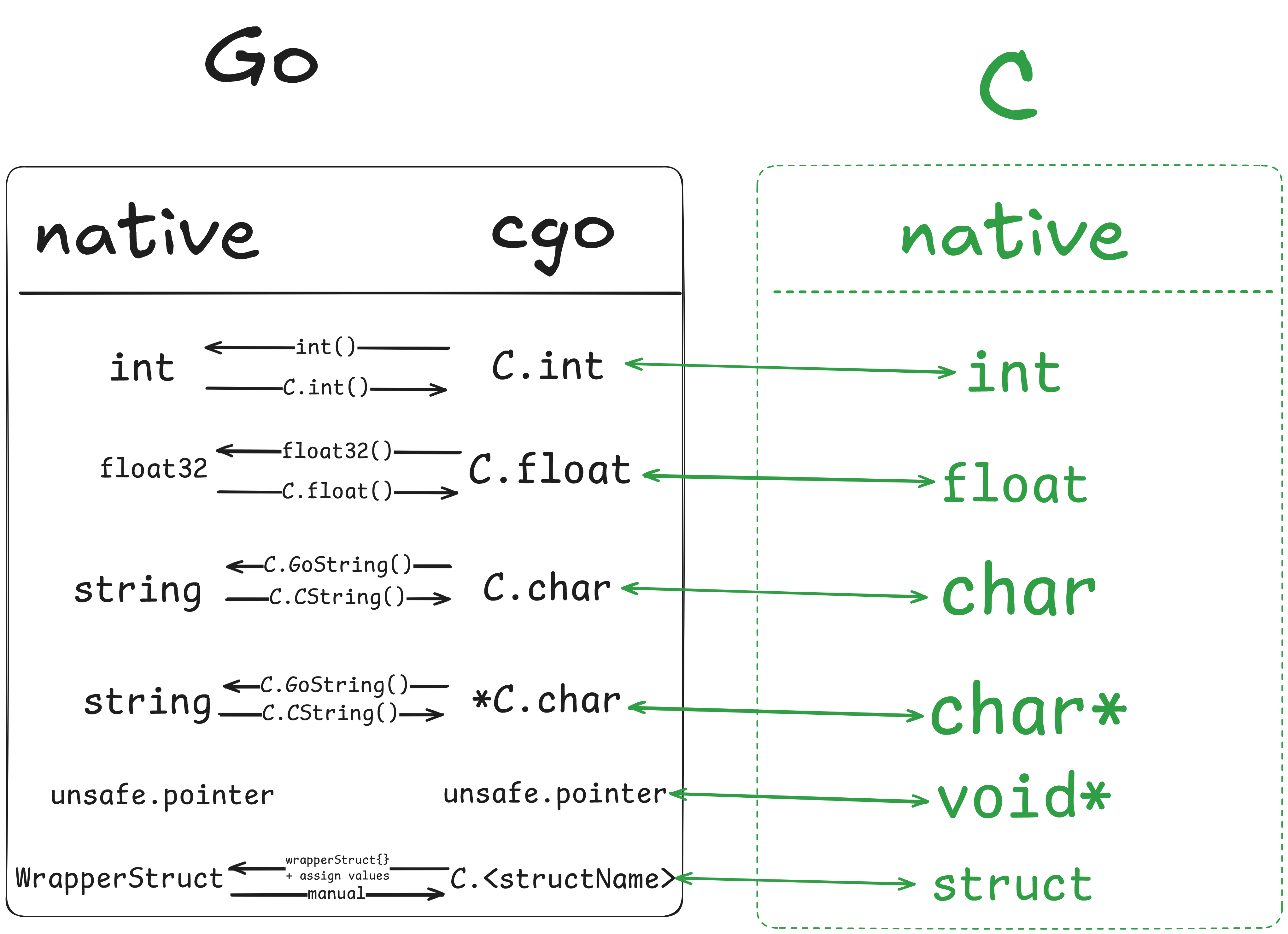

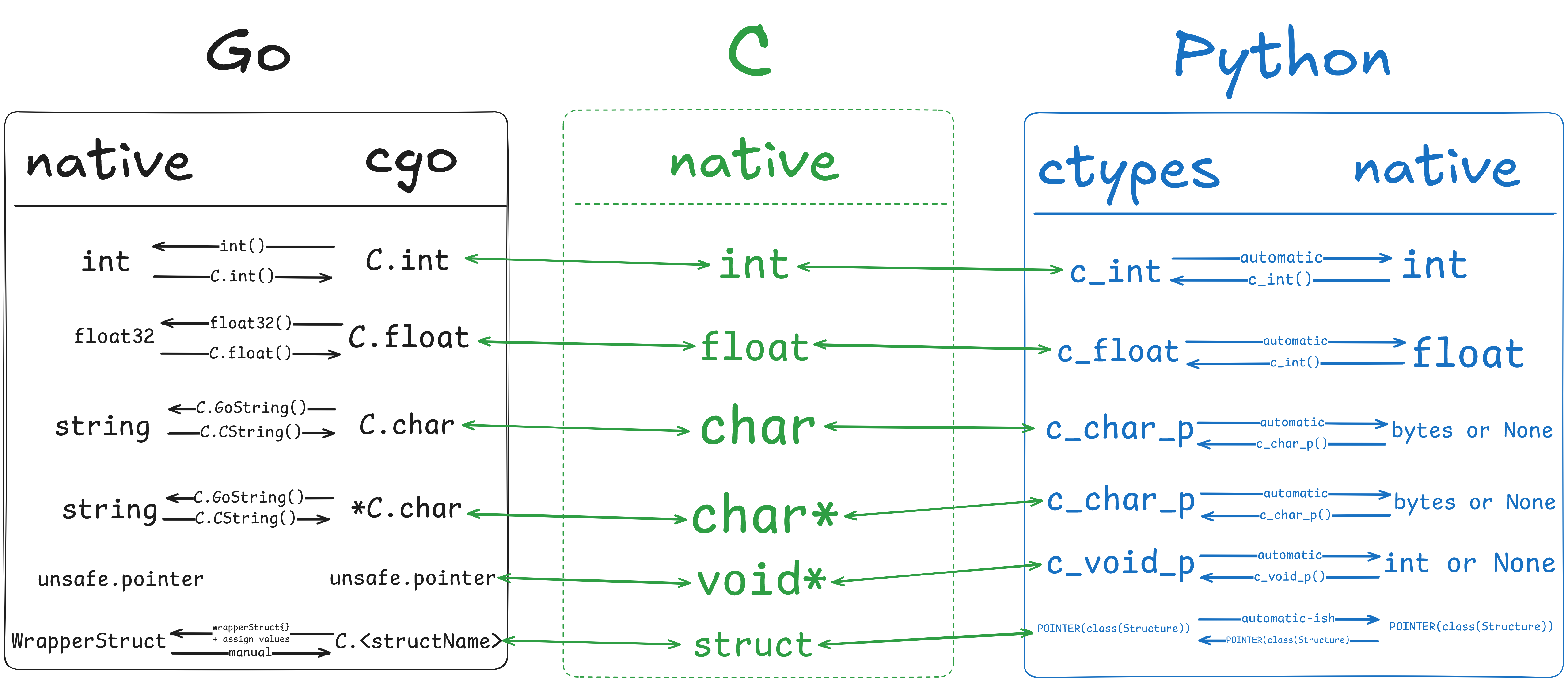

So, let’s see how this works for our Factorial() function. we will need to convert our Go types to C types, here are the equivalent types:

| go type | C type | cgo type | Python type |

|---|---|---|---|

string | char | C.char | str |

string | signed char | C.schar | str |

string | unsigned char | C.uchar | str |

int16 or int | short | C.short | int |

uint16 or int | unsigned short | C.ushort | int |

int | int | C.int | int |

uint | unsigned int | C.uint | int |

int32 or int | long | C.long | int |

uint32 or int | unsigned long | C.ulong | int |

int64 or int | long long | C.longlong | int |

uint64 or int | unsigned long long | C.ulonglong | int |

float32 | float | C.float | float |

float64 | double | C.double | float |

struct | struct | C.struct_<name_of_C_Struct> | class |

struct | union | C.union_<name_of_C_Union> | class |

struct | enum | C.enum_<name_of_C_Enum> | class |

unsafe.pointer | void* | unsafe.pointer | N/A |

*Please note that unions and enums are probably better left out of your code as much as you can, they’re very finicky

Or more simply:

*More about the bottom 4 in a bit

To convert from C to Go types to keep it simple I would use the functions of the table above, (i.e. int() to convert a C.int) except for:

C.GoString()(details later) for strings (C.char,*C.char, etc.)- Manually rebuild your structs (details later)

- Hide from

unsafe.Pointerunless you need it

Now we can finally convert our functions. For me I like to keep my python functions snake_case and my Go functions PascalCase to make it clear which is which. In this case that means just a lowercase version of the function as a wrapper:

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

)

// A function to greet someone

//

//export Greeting

func Greeting() {

fmt.Println("Hello from Go!")

}

// A function to calculate the factorial of a number n

func Factorial(n int) int {

result := n

lastVal := n - 1

for range int(n) {

if lastVal > 0 {

result *= lastVal

lastVal -= 1

}

}

return result

}

// The cgo binding to call the Factorial Function through

//

//export factorial

func factorial(n C.int) C.int {

goN := int(n) // Convert to go integer

result := Factorial(goN) // Get go integer result

r := C.int(result) // Convert to C integer

return r

}

func main() {

// This has to stay here, but leave it empty

}Now we can check if this works. We can build it using:

Linux/Mac

go build -buildmode=c-shared -o lib.so lib.go Windows

go build -buildmode=c-shared -o lib.dll lib.goIf you get an error saying something like:

# runtime/cgo

cc1: sorry, unimplemented: 64-bit mode not compiled inYou need to go back and setup your C compiler properly. If you now have two new files file called lib.dll/lib.so and lib.h you’re ready for the python part. Your folder should look something like this:

📂

├─ 📄go.mod

├─ 📄lib.go

├─ 📄lib.dll or 📄lib.so

└──📄lib.hPython

So to get started with python let’s create a new file called testing.py. Your directory should look like this after:

📂

├─ 📄testing.py

├─ 📄go.mod

├─ 📄lib.go

├─ 📄lib.dll or 📄lib.so

└──📄lib.hSo, now we’re going to use 2 built in python modules to help us import our code ctypes and platform. To import our file properly we will need ctypes.cdll.LoadLibrary(), and we will use the platform module to determine which file to load. Here’s the code:

from ctypes import cdll

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so") lib is now a CDLL, which acts similar to a python module. To keep things simple lets start with trying out the Greeting() function:

from ctypes import cdll

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

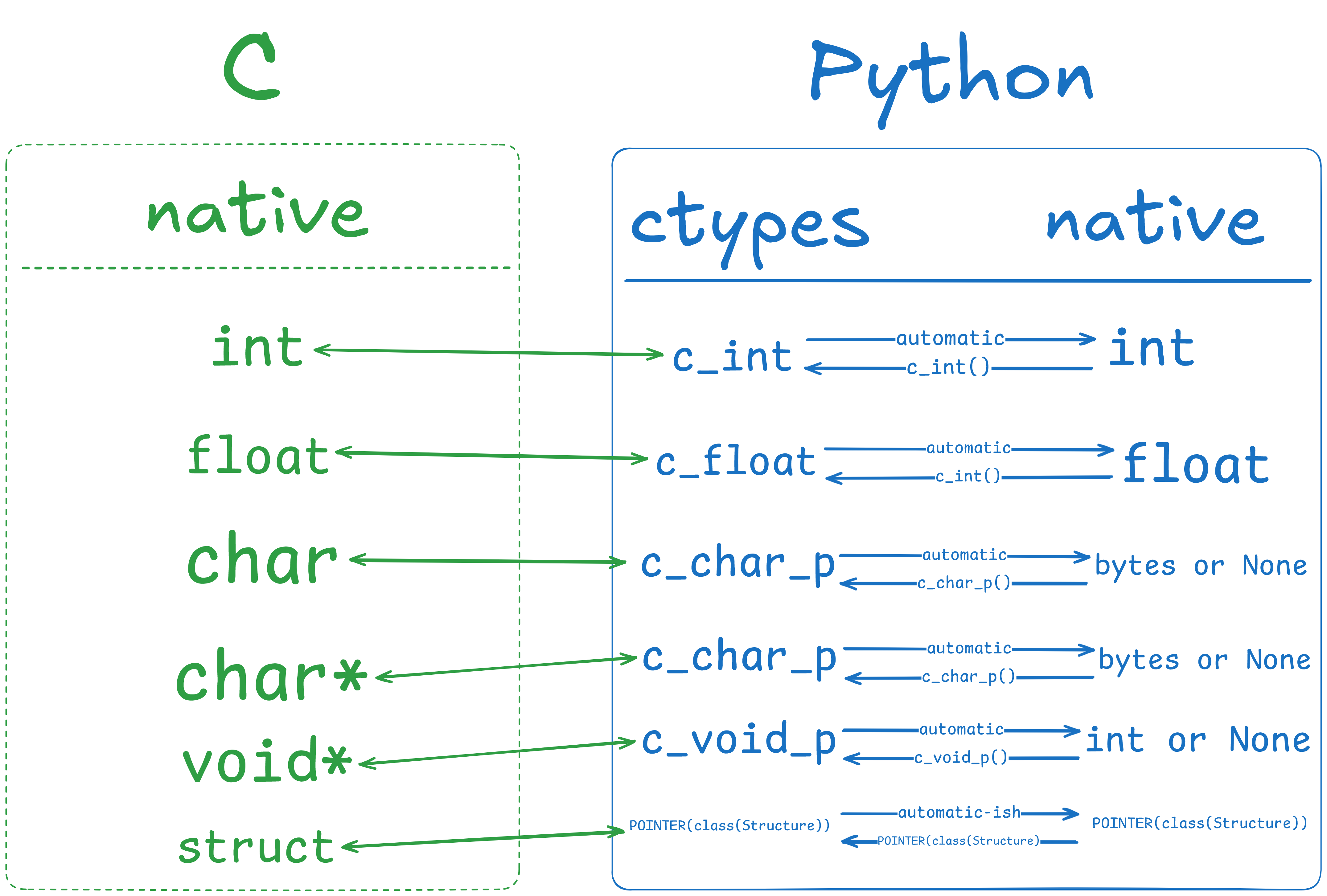

lib.Greeting()We get our original Hello from Go! great! Now for the variadic functions. Like go we have some custom types we need to be aware of to convert:

| Python type | C type | ctypes type |

|---|---|---|

bool | _Bool | c_bool |

1-character bytes object | char | c_char |

1-character str | wchar_t | c_wchar |

int | char | c_byte |

int | unsigned char | c_ubyte |

int | short | c_short |

int | unsigned short | c_ushort |

int | int | c_int |

int | unsigned int | c_uint |

int | long | c_long |

int | unsigned long | c_ulong |

int | __int64 or long long | c_longlong |

int | unsigned __int64 or unsigned long long | c_ulonglong |

int | size_t | c_size_t |

int | ssize_t or Py_ssize_t | c_ssize_t |

int | time_t | c_time_t |

float | float | c_float |

float | double | c_double |

float | long double | c_longdouble |

bytes object or None | char* (NUL terminated) | c_char_p |

str or None | wchar_t* (NUL terminated) | c_wchar_p |

int or None | void* | c_void_p |

*You can see an up-to-date version here

Or simply:

Now we know the types we have to tell python what the function takes in (argtypes) and returns restype, so for factorial() we do:

from ctypes import cdll, c_int

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup factorial function

lib.factorial.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.factorial.restype = c_intwe can then run it using:

n:int = 10

result = lib.factorial(10) # 3628800

type(result) # <class 'int'>Unlike go, python immediately converts the value from the function call for us. So the full data pipeline is:

The full code (collapsed for easy reading)

lib.go

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

)

// A function to greet someone

//

//export Greeting

func Greeting() {

fmt.Println("Hello from Go!")

}

// A function to calculate the factorial of a number n

//

// # Parameters

//

// n (int): The integer to calculate the factorial of

//

// # Returns

//

// int: The factorial of n

func Factorial(n int) int {

result := n

lastVal := n - 1

for range int(n) {

if lastVal > 0 {

result *= lastVal

lastVal -= 1

}

}

return result

}

// The cgo binding to call the Factorial Function through

//

// # Parameters

//

// n (C.int): The integer to calculate the factorial of

//

// # Returns

//

// C.int: The factorial of n

//

//export factorial

func factorial(n C.int) C.int {

goN := int(n) // Convert to go integer

result := Factorial(goN) // Get go integer result

r := C.int(result) // Convert to C integer

return r

}

func main() {

// This has to stay here, but leave it empty

}testing.py

from ctypes import cdll, c_int

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Simple idempotent function call

lib.Greeting()

# Variadic function (with arguments/returns)

lib.factorial.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.factorial.restype = c_int

n = 10

print(f"The factorial of {n} is {lib.factorial(n)} {type(lib.factorial(n))}")The hard part

Yes, all that really was the easy part, now comes some of the hard stuff. I want to make clear before we start this section I am not the best C programmer, so some of this is not easy for me either. There may be better ways to handle this that I’m not aware of, but I’m doing my best here. To put it bluntly the hard part of all this is memory management. Compared to even traditional C this sort of memory management is harder than you would think because you need to synchronize everything together. The fact that multiple environments are accessing shared memory makes it incredibly easy to accidentally double-free, memory leak, NULL dereference and use-after-free (amoung other vulnerabilities).

So I will share some tips at the end for rules to follow to help avoid these problems.

Strings

To understand this for those of us that don’t use C much, the reason strings are awkward is because strings don’t really exist. Strings are just an array of bytes, essentially a chunk of memory, with a bit of data in it. From there we interpret each byte according to it’s encoding. For strings this means we might get something like this:

In this case that means our string is just actually a pointer to the first byte (0x48), and then we keep track of the length 6 bytes. So our “string” is just an array of [0x48, 0x65, 0x6C, 0x6C, 0x6F, 0x00] in C. When we want to use the string, we then chuck those raw bytes through an encoding (in this case ASCII) to get the characters back out again. But, the length is variable, so the only thing we store is the pointer to the first byte (hence char* being a pointer to the first char), and we handle the length ourselves. Unlike integers or floating point numbers which all have a fixed size, making it so C can clean them up for us. Because of this we also have to handle cleanup ourselves (with C.free() and a pointer to the data). This cleanup is dangerous because we are responsible, which means if we’re wrong, we can do some damage.

Working with strings the way I will explain is not terrible because for the most part we are just taking that string, converting it to a go/python string, and working with it internally in the language. Anything that is internal to Go is managed by Go, anything that crosses the go-python boundary, handle the cleanup in python (with some help from go).

With that said, here’s some example code that looks similar to what we’ve seen before:

// A function that generates a string to greet someone

func GreetS(name string) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Hello %s!\nHow's your day?\n", name)

}So in this case we have a string being passed in, and one being returned.

Now comes the hairy part of this. You can free the memory in the go function, I would recommend using defer if you decide to. However, python considers itself responsible for certain datatypes that it creates. name is passed in from python, which means that python will clean the memory itself!

The below code for example WILL NOT WORK WITH PYTHON, but might be useful if you’re writing code for C or other memory unmanaged languages:

//export greet_string

func greet_string(name *C.char) *C.char {

defer C.free(unsafe.Pointer(name)) // Clean up memory at the end of the function

goName := C.GoString(name) // Convert input to go string

result := fmt.Sprintf("HELLO %s", goName) // Get a result as a go string

return C.CString(result) // Return a C-compatible string

}So, returning back to our code that does work (without the C.free()), we can look at how it works in python:

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup our functions

lib.greet_string.argtypes = [c_char_p]

lib.greet_string.restype = c_char_p

name = "Kieran".encode()

result:bytes = lib.greet_string(name)

print(f"The result is {result.decode(errors='replace')}")*When decoding I did errors='replace' there are some weird encoding errors when using encoding='strict' (the default) that I encountered, so this is a more relaxed decoding, but it could lead to issues depending on your character set

Now if we compile the go code, and run the python code, everything works so we’re all good right? Wrong, we actually just leaked some memory by accident. Like I said before, variables created by python are managed by it, so our name variable will be cleaned up properly, but we never cleaned up the result variable. When python created name it took ownership of the memory, and when it passed it in, it still had ownership. When we created the result variable, it was created in Go using C.Cstring, which ran malloc() (a custom version of it) under the hood. So the memory was created in C by go, but it’s never told when the reference dies, so it’s never GC’d. Here’s a diagram following the execution of the python program:

To fix this we can write a go function that takes in a C string and frees it:

//export free_string

func free_string(str *C.char) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(str))

}Then we can call the new free_string() function in our python code:

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.greet_string.argtypes = [c_char_p]

lib.greet_string.restype = c_char_p

lib.free_string.argtypes = [c_char_p]

lib.free_string.restype = None

name = "Kieran".encode()

result:bytes = lib.greet_string(name)

print(f"The result is {result.decode(errors='replace')}")

lib.free_string(result)Perfect, so we’re good right? Kinda, but here’s why we use languages like Go and python in the first place. How do you know you’re doing the right thing with lib.free_string()? What happens if an error occurs right after we allocate result? The memory is never cleaned.

The harsh reality is that you just need to always be careful no matter what your solution is. I tried about 15 different ones during the writting of this article, and the reality is that there’s no silver bullet. The best of the janky potential “solutions” I can suggest __del__() and try finally. try finally is the easiest, you just do something like this:

... # Other code above

name = "Kieran".encode()

result = lib.greet_string(name)

try:

print(f"The result is {result.decode(errors='replace')}")

finally:

lib.free_string(result)The finally keyword means that even if there’s an error after result is created, lib.free_string(result) will be run. This works pretty well, but we need to remember to do it, and it can get complicated if we do something like this:

name = "Kieran".encode()

result = lib.greet_string(name)

try:

result2 = lib.greet_string(name)

print(f"The result is {result.decode(errors='replace')}")

finally:

lib.free_string(result)

lib.free_string(result2)What happens if an error occurs while result2 is being assigned? Then when we free in our finally block, we’re freeing unused memory, which is bad, my head hurts. This solution is not great, and in general you should try to avoid it by itself unless you’re passing and receiving 1 variable at a time.

Behind janky door number 2 is __del__(). This is a dunder/magic method that allows you to override what happens when python cleans up objects. This isn’t a very handy option for this example, but when we start looking at classes below it will be. Let’s see how this could work for our above example first:

class EvilString(str):

def __init__(self:'EvilString', value:bytes) -> 'EvilString':

self.value = value

def __str__(self) -> str:

return self.value.decode(errors='replace')

def __del__(self):

lib.free_string(self.value)So, when we ask python to convert the value to a string, we get what we expect, and python will automatically clean up the references when we no longer need them, great right? You probably know where this is going. Here’s some code:

... # Other code

class EvilString(str):

def __init__(self:'EvilString', value:bytes) -> 'EvilString':

self.value = value

def __str__(self) -> str:

return self.value.decode(errors='replace')

def __del__(self):

lib.free_string(self.value)

name = "Kieran".encode()

name2 = "Kieran2".encode()

result = EvilString(lib.greet_string(name))

print(f"The result is: {result}")

result2:str = str(EvilString(lib.greet_string(name2)))

print(f"The result is: {result2}")So what’s the issue? The first result variable is great, no issues! But the second print statement never happens. The program silently crashes before it runs. No traceback, no errors, just dies. The output is actually this:

$> python testing.py

The result is: Hello Kieran

How's your day?

Deallocating string Hello Kieran2

How's your day?So what’s wrong here. It’s actually the string conversion for result2 the lines are:

name2 = "Kieran2".encode()

result2:str = str(EvilString(lib.greet_string(name2)))To make things complicated, you would assume the code below is equivalent, but actually this code would work:

name2 = "Kieran2".encode()

step1 = lib.greet_string(name2)

step2 = EvilString(step1)

result2:str = str(step2)Looking at the print logs we can see what’s happening. The reason is how python handles objects. Python counts references, and then cleans when nothing else needs it. Because we’re only creating the EvilString to run the str() on it in the original code, the EvilString value is GC’d after str() runs on it. This means the reference to the underlying value is dereferenced before the print() call is made, so the first code would actually expand under the hood to look like this:

name2 = "Kieran2".encode()

step1 = lib.greet_string(name2)

step2 = EvilString(step1)

result2:str = str(step2)

del step2 # Also breaks result2 because the pointer to the value is gone

print(f"The result is: {result2}")Here’s a diagram of what’s happening:

So this approach also has it’s own problems to watch out for. Like I said, there’s no silver bullet, this sort of programming is just hard sometimes.

The full code (collapsed for easy reading)

lib.go

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

*/

import "C"

import (

"fmt"

"unsafe"

)

// A function that generates a string to greet someone

//

// # Parameters

//

// name(string): The name of the person being greeted

//

// # Returns

//

// string: a greeting

func GreetS(name string) string {

return fmt.Sprintf("Hello %s\nHow's your day?\n", name)

}

// A function that generates a string to greet someone

//

// # Parameters

//

// name(*C.char): The name of the person being greeted

//

// # Returns

//

// *C.char: a greeting to display to the user

//

//export greet_string

func greet_string(name *C.char) *C.char {

goName := C.GoString(name) // Convert input to go string

result := GreetS(goName) // Get a result as a go string

return C.CString(result) // Return a C-compatible string

}

// Used to free a C string after use

//

// # Parameters

//

// str (*C.char): The string to free

//

//export free_string

func free_string(str *C.char) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(str))

}

func main() {

// This has to stay here, but leave it empty

}testing.py

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p

from platform import platform

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.greet_string.argtypes = [c_char_p]

lib.greet_string.restype = c_char_p

lib.free_string.argtypes = [c_char_p]

lib.free_string.restype = None

# Manually cleaning up memory

name2 = "Kieran".encode()

result2:str = lib.greet_string(name2)

print(f"The result is: {result2.decode(errors='replace')}")

lib.free_string(result2)

# Class-based approach with __del__()

class EvilString(str):

def __init__(self:'EvilString', value:bytes) -> 'EvilString':

self.value = value

def __str__(self) -> str:

return self.value.decode(errors='replace')

def __del__(self):

lib.free_string(self.value)

name = "Kieran".encode()

result = EvilString(lib.greet_string(name))

print(f"The result is: {result}")

# Below code errors out

# name2 = "Kieran2".encode()

# result2:str = str(EvilString(lib.greet_string(name2)))

# print(f"The result is: {result2}")Classes & Slices

Classes & slices is where the memory issues get cranked up to 11. For our “simpler” types (ints, floats, etc.) there is a set length (i.e. int8 is always a set size), which means it’s easier to pass around because you have certain guarentees for sizes. For strings, C stores just the bytes, the encoding is a separate system that’s up to whatever is interpreting those bytes. The same is true for structs & slices, we need to allocate the space for the struct/slices ourselves, and manage how much memory is needed ourselves. Imagine the struct:

type User struct {

name string

age int

email string

}The C equivalent would be:

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct{

char* name;

int age;

char* email;

} User;So to create this struct we would need to allocate enough space for:

- The two char pointers (The data is a separate allocation)

- The integer

To do this, we need to create the struct in go, and add the equivalent struct to our C environment. It looks something like this:

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct{

char* name;

int age;

char* email;

} User;

*/

import "C"

type User struct {

name string

age int

email string

}We now have a type of C.User that is created and looks something like this:

type C.User struct{

name *C.char

age C.int

email *C.char

}So, to create a C.User and return it in a function we first allocate the memory for the struct. Since we’re constructing the struct in go, this requires knowing the size, then running C.malloc() and casting the resulting pointer to our new type:

func create_user(name *C.char, age C.int, email *C.char) *C.User{

// Get the estimated size

memoryFootprint := unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})

// Convert to the actual size

CMemoryFootprint := C.size_t(memoryFootprint)

// allocate the struct and cast to a `C.User` pointer

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(CMemoryFootprint))

}Once we’ve allocted, now we can create the struct with our values and return it:

//export create_user

func create_user(name *C.char, age C.int, email *C.char) *C.User {

// allocate the struct

memoryFootprint := unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})

CMemoryFootprint := C.size_t(memoryFootprint)

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(CMemoryFootprint))

// Instantiate the struct with it's values

*user = C.User{

name: C.CString(C.GoString(name)),

age: age,

email: C.CString(C.GoString(email)),

}

return user

}You may be wondering why we didn’t have to do any fancy allocations for name and email, we don’t have to because C.CString() handles that complexity for us. To be safe, get in the habit of writing a free function after you add a C struct in. So in our case we would have:

//export free_user

func free_user(userReference *C.User) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.name))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.email))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference))

}Here comes the tricky bit. You see in our free_user function we’re freeing the name, email, then the whole struct, but what about age? Well, like I said before int and other primitive types have set lengths, and C will deal with it for us, so we don’t need to de-allocate them manually. But we do have to free the memory for the two strings, since they were dynamically allocated (same is true if you use C.malloc() for anything). So, we get the pointer to the string using unsafe.Pointer, and free it. Once we’ve cleaned up the values for individual values of the struct, then clean the struct.

Now, let’s look at a useful pattern for tying this together with python.

Pattern for classes

First things first, to make this work you will have to create 4 separate struct/classes. The first 2 are in Go and CGo, and the other 2 are in python. This seems like a lot (and it is), but this is for a good reason. You can do it other ways, but this is what I recommend.

Lets start with a modified version of the go code we saw before:

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct{

char* name;

int age;

char* email;

} User;

*/

import "C"

import (

"github.com/brianvoe/gofakeit"

)

type User struct {

name string

age int

email string

}

func createRandomUser() *User {

return &User{gofakeit.Name(), gofakeit.Number(13, 90), gofakeit.Email()}

}

//export create_user

func create_user(name *C.char, age C.int, email *C.char) *C.User {

// allocate the struct

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}))))

// Create the struct and it's poitners

*user = C.User{

name: C.CString(C.GoString(name)),

age: age,

email: C.CString(C.GoString(email)),

}

return user

}

//export create_random_user

func create_random_user() *C.User {

// Create a random go version of the user

res := createRandomUser()

// Create C-compatible versions of variables

cName := C.CString(res.name)

cEmail := C.CString(res.email)

// Allocate necessary memory

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}))))

// Assign values to freshly created struct

user.name = cName

user.age = C.int(res.age)

user.email = cEmail

return user

}

//export free_user

func free_user(userReference *C.User) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.name))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.email))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference))

}

func main() {

// Do nothing

}Make sure to run go mod tidy to download the library from github. We can now use this to create random User’s and then pipe those out as a C.User via the create_random_user() function. So our first two structs are down (User and C.User). Now we need the python side, so let’s create those two classes first, and bring in the rest of the code slowly:

from dataclasses import dataclass

from ctypes import c_char_p, c_int, Structure

# Define the C-compatible User struct in Python

class CUser(Structure):

_fields_ = [

("name", c_char_p),

("age", c_int),

("email", c_char_p),

]

# The pure python class

@dataclass

class User:

name:str

age:int

email:strNow let’s setup those functions from before, to do this we will use a POINTER object that wraps our CUser struct:

from platform import platform

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p, c_int, Structure, POINTER

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.free_user.argtypes = [POINTER(CUser)]

lib.create_random_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)

lib.create_user.argtypes = [c_char_p, c_int, c_char_p]

lib.create_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)We can then use the code with:

try:

user_pointer = lib.create_user("Kieran".encode(), 21, "[email protected]".encode())

print(user_pointer) # <__main__.LP_CUser object at 0x0000022BE95AD650>

print(user_pointer.contents) # <__main__.CUser object at 0x0000022BE95AD5D0>

# Prints: user_pointer.contents.name=b'Kieran', user_pointer.contents.age=21, user_pointer.contents.email=b'[email protected]'

print(f"{user_pointer.contents.name=}, {user_pointer.contents.age=}, {user_pointer.contents.email=}")

finally:

lib.free_user(user_pointer)

print("Cleared user")So you can see we have the pointer (of type LP_CUser), and then the contents can be found in LP_CUser.contents (of type CUser). Remember that our strings come in as a Bytes, that we need to encode() to get the text back out. So, to make this easier, let’s modify our User class so that we can add a class method to instantiate it via Go/C:

import traceback

from dataclass import dataclass

@dataclass

class User:

name:str

age:int

email:str

@classmethod

def create_user_from_C(cls:'User', name:str, age:int, email:str) -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_user(name.encode(encoding="utf-8"), age, email.encode(encoding="utf-8"))

data = pointer.contents

try:

assert data.name.decode() == name

assert data.age == age

assert data.email.decode() == email

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)

@classmethod

def create_random_user(cls:'User') -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_random_user()

data = pointer.contents

try:

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)Then to use the class we can do:

me = User.create_user_from_C("Kieran", 26, "[email protected]")

rando = User.create_random_user()

print(me) # User(name='Kieran', age=26, email='[email protected]')

print(rando) # User(name='Pearl Pagac', age=40, email='[email protected]')To understand the memory here’s a diagram:

The full code (collapsed for easy reading)

lib.go

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct{

char* name;

int age;

char* email;

} User;

*/

import "C"

import (

"unsafe"

"github.com/brianvoe/gofakeit"

)

type User struct {

name string

age int

email string

}

func createRandomUser() *User {

return &User{gofakeit.Name(), gofakeit.Number(13, 90), gofakeit.Email()}

}

func CreateRandomUsers(count int) *[]User {

result := make([]User, count)

for i := range count {

result[i] = *createRandomUser()

}

return &result

}

//export create_user

func create_user(name *C.char, age C.int, email *C.char) *C.User {

// allocate the struct

memoryFootprint := unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})

CMemoryFootprint := C.size_t(memoryFootprint)

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(CMemoryFootprint))

// Create the struct and it's poitners

*user = C.User{

name: C.CString(C.GoString(name)),

age: age,

email: C.CString(C.GoString(email)),

}

return user

}

//export create_random_user

func create_random_user() *C.User {

// Create a random go version of the user

res := createRandomUser()

// Expand go versions of variables

goName := res.name

goEmail := res.email

age := res.age

// Create C-compatible versions of variables

cName := C.CString(goName)

cEmail := C.CString(goEmail)

// Allocate necessary memory

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}))))

// Assign values to freshly created struct

user.name = cName

user.age = C.int(age)

user.email = cEmail

return user

}

//export free_user

func free_user(userReference *C.User) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.name))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.email))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference))

}

func main() {

// Do nothing

}

testing.py

import traceback

from platform import platform

from dataclasses import dataclass

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p, c_int, Structure, POINTER

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Define the C-compatible User struct in Python

class CUser(Structure):

_fields_ = [

("name", c_char_p),

("age", c_int),

("email", c_char_p),

]

# Setup functions

lib.free_user.argtypes = [POINTER(CUser)]

lib.create_random_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)

lib.create_user.argtypes = [c_char_p, c_int, c_char_p]

lib.create_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)

try:

user_pointer = lib.create_user("Kieran".encode(), 21, "[email protected]".encode())

print(user_pointer)

print(user_pointer.contents)

print(f"{user_pointer.contents.name=}, {user_pointer.contents.age=}, {user_pointer.contents.email=}")

finally:

lib.free_user(user_pointer)

print("Cleared user")

@dataclass

class User:

name:str

age:int

email:str

@classmethod

def create_user_from_C(cls:'User', name:str, age:int, email:str) -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_user(name.encode(encoding="utf-8"), age, email.encode(encoding="utf-8"))

data = pointer.contents

try:

assert data.name.decode() == name

assert data.age == age

assert data.email.decode() == email

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Something went wrong, free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)

@classmethod

def create_random_user(cls:'User') -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_random_user()

data = pointer.contents

try:

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Something went wrong, free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)

me = User.create_user_from_C("Kieran", 26, "[email protected]")

rando = User.create_random_user()

print(me)

print(rando)Slices

Slices also get a bit weird, but the pattern is a bit simpler for them. Take a function that returns a slice, say:

func Fib(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return 1

} else {

return Fib(n-2) + Fib(n-1)

}

}

func FibSequence(n int) []int {

results := make([]int, 0, n)

for i := 0; i < int(n); i++ {

results = append(results, Fib(i))

}

return results

}Typically with integers we don’t need to mess around with pointers. If we wanted to wrap Fib() for example, we could just do:

func fib(n C.int) C.int{

res := Fib(int(n))

return C.int(res)

}But with a slice we take the base type, and add an extra pointer, so for an integer slice, like FibSequence() we do:

func fib_sequence(n C.int) *C.int {

// Code in here

}So at the end we need a pointer to the integers, got it. Now we can first get our results from FibSequence(), then we need to do pointer arithmetic. Essentially we need to calculate the size of the array, and allocate that memory. We can do that with this:

// Allocate memory for an array of C ints (int*)

sizeOfArray := C.size_t(n)

sizeOfEachElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)))

amountOfMemory := sizeOfArray * sizeOfEachElement

// Allocate the necessary memory

cArray := (*C.int)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))Now that we have the array, we need to fill it with data. To do this we determine the starting location of the array, the size of each element, and the current index/offset into the array:

// Create Array of data

for i, currentNumber := range results {

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(cArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfEachElement := unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)) // Size of a single value

locationInMemory := (*C.int)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfEachElement))

*locationInMemory = C.int(currentNumber) // Convert go int to C int and insert at location in array

}So since our memory is allocated, we’re manually casting our location in memory to a pointer of a C.int then filling it with data in the last line. We do this for each element, and we’ve manually allocated and filled our array. All together it looks like this:

//export fib_sequence

func fib_sequence(n C.int) *C.int {

results := FibSequence(int(n))

// Allocate memory for an array of C ints (int*)

sizeOfArray := C.size_t(n)

sizeOfEachElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)))

amountOfMemory := sizeOfArray * sizeOfEachElement

cArray := (*C.int)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))

// Create Array of data

for i, currentNumber := range results {

// Calculate where to put the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(cArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfEachElement := unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)) // Size of a single value

locationInMemory := (*C.int)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfEachElement))

*locationInMemory = C.int(currentNumber) // Convert go int to C int and insert at location in array

}

return cArray

}Now we just setup a function to clean up our array, which is pretty easy since integers are a fixed size:

//export free_int_array

func free_int_array(array *C.int) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(array))

}Now we write and test the python side:

from platform import platform

from ctypes import cdll, c_int, POINTER

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.fib_sequence.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.fib_sequence.restype = POINTER(c_int)

lib.free_int_array.argtypes = [POINTER(c_int)]

n = 10

ptr = lib.fib_sequence(n)

try:

results = []

for i in range(n):

results.append(ptr[i])

print(results) # [1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55]

finally:

lib.free_int_array(ptr)The full code (collapsed for easy reading)

lib.go

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

*/

import "C"

import "unsafe"

func Fib(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return 1

} else {

return Fib(n-2) + Fib(n-1)

}

}

func FibSequence(n int) []int {

results := make([]int, 0, n)

for i := 0; i < int(n); i++ {

results = append(results, Fib(i))

}

return results

}

//export fib_sequence

func fib_sequence(n C.int) *C.int {

results := FibSequence(int(n))

// Allocate memory for an array of C ints (int*)

sizeOfArray := C.size_t(n)

sizeOfEachElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)))

amountOfMemory := sizeOfArray * sizeOfEachElement

cArray := (*C.int)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))

// Create Array of data

for i, currentNumber := range results {

// Calculate where to put the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(cArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfEachElement := unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)) // Size of a single value

locationInMemory := (*C.int)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfEachElement))

*locationInMemory = C.int(currentNumber) // Convert go int to C int and insert at location in array

}

return cArray

}

//export free_int_array

func free_int_array(array *C.int) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(array))

}

func main() {

// Do nothing

}testing.py

from platform import platform

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p, c_int, POINTER

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.fib_sequence.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.fib_sequence.restype = POINTER(c_int)

lib.free_int_array.argtypes = [POINTER(c_int)]

n = 10

ptr = lib.fib_sequence(n)

try:

results = []

for i in range(n):

results.append(ptr[i])

print(results)

finally:

lib.free_int_array(ptr)This will work for any of the simple types, but what about strings and structs?

All together now

This leads to our final question, how do we return an array of structs/strings. For both the answer is the same. We combine what we learned about slices with what we learned about structs and strings. Here’s a bit of go code that takes in a string, and multiplies it by a number suggested, then returns a string slice of those values:

func MultiplyString(inputString string, count int) []string {

result := make([]string, 0, count)

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

result = append(result, inputString)

}

return result

}Like I said before, we take our result type and add another pointer to it. So, since we usually return *C.char for strings, we instead use **C.char:

func multiply_string(inputString *C.char, count C.int) **C.char {

// code here

}Everything else looks pretty familiar, we allocate our memory:

// Allocate memory for an array of C string pointers (char**)

amountOfElements := C.size_t(count)

sizeOfSingleElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)))

amountOfMemory := amountOfElements * sizeOfSingleElement

stringArray := (**C.char)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))*Weirdly enough for strings we use uintptr(0) since the “size” is actually just the size of the pointer. For structs you use an empty struct, i.e. for a C.User struct from earlier you would use unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})

Then fill with our data:

// Create Array of data

for i, currentString := range res {

// Calculate where to put the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(stringArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfSingleElement := unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)) // Size of a single string

locationInMemory := (**C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfSingleElement))

*locationInMemory = C.CString(currentString) // Convert go string to C string and insert at location in array

}Make sure we add a function to clean everything up:

//export free_string_array

func free_string_array(inputArray **C.char, count C.int) {

for i := 0; i < int(count); i++ {

// Calculate where to find the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(inputArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

memorySizeOfStruct := unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)) // Size of a single struct

ptr := *(**C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*memorySizeOfStruct))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(ptr))

}

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(inputArray))

}Then in python:

# Setup functions

lib.multiply_string.argtypes = [c_char_p, c_int]

lib.multiply_string.restype = POINTER(c_char_p)

lib.free_string_array.argtypes = [POINTER(c_char_p), c_int]

count = 5

r = lib.multiply_string("Hello".encode(), count)

try:

result = []

for i in range(count):

result.append(r[i].decode(errors='replace'))

print(result) # ['Hello', 'Hello', 'Hello', 'Hello', 'Hello']

finally:

lib.free_string_array(r, count)You can find the full code below, with an additional example with a struct

The full code (collapsed for easy reading)

lib.go

package main

/*

#include <stdlib.h>

typedef struct{

char* name;

int age;

char* email;

} User;

*/

import "C"

import (

"unsafe"

"github.com/brianvoe/gofakeit"

)

func Fib(n int) int {

if n < 2 {

return 1

} else {

return Fib(n-2) + Fib(n-1)

}

}

func FibSequence(n int) []int {

results := make([]int, 0, n)

for i := 0; i < int(n); i++ {

results = append(results, Fib(i))

}

return results

}

//export fib_sequence

func fib_sequence(n C.int) *C.int {

results := FibSequence(int(n))

// Allocate memory for an array of C ints (int*)

sizeOfArray := C.size_t(n)

sizeOfEachElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)))

amountOfMemory := sizeOfArray * sizeOfEachElement

cArray := (*C.int)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))

// Create Array of data

for i, currentNumber := range results {

// Calculate where to put the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(cArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfEachElement := unsafe.Sizeof(C.int(0)) // Size of a single value

locationInMemory := (*C.int)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfEachElement))

*locationInMemory = C.int(currentNumber) // Convert go int to C int and insert at location in array

}

return cArray

}

//export free_int_array

func free_int_array(array *C.int) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(array))

}

func MultiplyString(inputString string, count int) []string {

result := make([]string, 0, count)

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

result = append(result, inputString)

}

return result

}

//export multiply_string

func multiply_string(inputString *C.char, count C.int) **C.char {

res := MultiplyString(C.GoString(inputString), int(count))

// Allocate memory for an array of C string pointers (char**)

amountOfElements := C.size_t(count)

sizeOfSingleElement := C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)))

amountOfMemory := amountOfElements * sizeOfSingleElement

stringArray := (**C.char)(C.malloc(amountOfMemory))

// Create Array of data

for i, currentString := range res {

// Calculate where to put the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(stringArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfSingleElement := unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)) // Size of a single string

locationInMemory := (**C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfSingleElement))

*locationInMemory = C.CString(currentString) // Convert go string to C string and insert at location in array

}

return stringArray

}

//export free_string_array

func free_string_array(inputArray **C.char, count C.int) {

for i := 0; i < int(count); i++ {

// Calculate where to find the string

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(inputArray)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

memorySizeOfStruct := unsafe.Sizeof(uintptr(0)) // Size of a single struct

ptr := *(**C.char)(unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*memorySizeOfStruct))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(ptr))

}

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(inputArray))

}

type User struct {

name string

age int

email string

}

func createRandomUser() *User {

return &User{gofakeit.Name(), gofakeit.Number(13, 90), gofakeit.Email()}

}

func CreateRandomUsers(count int) []*User {

result := make([]*User, count)

for i := 0; i < count; i++ {

result[i] = createRandomUser()

}

return result

}

//export create_user

func create_user(name *C.char, age C.int, email *C.char) *C.User {

// allocate the struct

memoryFootprint := unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})

CMemoryFootprint := C.size_t(memoryFootprint)

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(CMemoryFootprint))

// Create the struct and it's poitners

*user = C.User{

name: C.CString(C.GoString(name)),

age: age,

email: C.CString(C.GoString(email)),

}

return user

}

//export create_random_user

func create_random_user() *C.User {

// Create a random go version of the user

res := createRandomUser()

// Expand go versions of variables

goName := res.name

goEmail := res.email

age := res.age

// Create C-compatible versions of variables

cName := C.CString(goName)

cEmail := C.CString(goEmail)

// Allocate necessary memory

user := (*C.User)(C.malloc(C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}))))

// Assign values to freshly created struct

user.name = cName

user.age = C.int(age)

user.email = cEmail

return user

}

//export create_random_users

func create_random_users(count C.int) *C.User {

// Create a random go version of the user

res := CreateRandomUsers(int(count))

users := (*C.User)(C.malloc(C.size_t(count) * C.size_t(unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}))))

// Create Array of data

for i, user := range res {

locationOfArray := uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(users)) // Starting point of first byte of slice

offsetIntoArray := uintptr(i) // The offset for the current element

sizeOfSingleStruct := unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{}) // Size of a single struct

// Calculate where to put the current struct

startPoint := unsafe.Pointer(locationOfArray + offsetIntoArray*sizeOfSingleStruct)

// Get pointer location for current struct

currentUser := (*C.User)(startPoint)

// Assign values to new C.User struct

currentUser.name = C.CString(user.name)

currentUser.age = C.int(user.age)

currentUser.email = C.CString(user.email)

}

return users

}

//export free_user

func free_user(userReference *C.User) {

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.name))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference.email))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(userReference))

}

//export free_users

func free_users(users *C.User, count C.int) {

for i := range int(count) {

currentUserPointer := (*C.User)(unsafe.Pointer(uintptr(unsafe.Pointer(users)) + uintptr(i)*unsafe.Sizeof(C.User{})))

// Clear strings

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(currentUserPointer.name))

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(currentUserPointer.email))

}

C.free(unsafe.Pointer(users))

}

func main() {

// Do nothing

}testing.py

import traceback

from dataclasses import dataclass

from platform import platform

from ctypes import cdll, c_char_p, c_int, POINTER, Structure

# import library

if platform().lower().startswith("windows"):

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.dll")

else:

lib = cdll.LoadLibrary("./lib.so")

# Setup functions

lib.fib_sequence.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.fib_sequence.restype = POINTER(c_int)

lib.free_int_array.argtypes = [POINTER(c_int)]

lib.multiply_string.argtypes = [c_char_p, c_int]

lib.multiply_string.restype = POINTER(c_char_p)

lib.free_string_array.argtypes = [POINTER(c_char_p), c_int]

n = 10

ptr = lib.fib_sequence(n)

try:

results = []

for i in range(n):

results.append(ptr[i])

print(results)

finally:

lib.free_int_array(ptr)

count = 5

r = lib.multiply_string("Hello".encode(), count)

try:

result = []

for i in range(count):

result.append(r[i].decode(errors='replace'))

print(result)

finally:

lib.free_string_array(r, count)

# User demo

class CUser(Structure):

_fields_ = [

("name", c_char_p),

("age", c_int),

("email", c_char_p),

]

lib.free_user.argtypes = [POINTER(CUser)]

lib.create_random_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)

lib.create_user.argtypes = [c_char_p, c_int, c_char_p]

lib.create_user.restype = POINTER(CUser)

lib.create_random_users.argtypes = [c_int]

lib.create_random_users.restype = POINTER(CUser)

lib.free_users.argtypes = [POINTER(CUser), c_int]

@dataclass

class User:

name:str

age:int

email:str

@classmethod

def create_user_from_C(cls:'User', name:str, age:int, email:str) -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_user(name.encode(encoding="utf-8"), age, email.encode(encoding="utf-8"))

data = pointer.contents

try:

assert data.name.decode() == name

assert data.age == age

assert data.email.decode() == email

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Something went wrong, free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)

@classmethod

def create_random_user(cls:'User') -> 'User':

pointer = lib.create_random_user()

data = pointer.contents

try:

return User(data.name.decode(errors="replace"), data.age, data.email.decode(errors="replace"))

except (AssertionError, UnicodeDecodeError) as e:

raise ValueError(f"Could not instantiate User\n\t{repr(traceback.format_exception(e))}")

finally:

# Something went wrong, free the memory

lib.free_user(pointer)

@classmethod

def create_random_users(cls:'User', count:int) -> list['User']:

results = []

pointer = lib.create_random_users(count)

if not pointer:

raise ValueError("Failed to parse URLs")

try:

for i in range(count):

site_ptr = pointer[i]

data = site_ptr

try:

results.append(cls(

name=data.name.decode(errors="replace"),

age=data.age,

email=data.email.decode(errors="replace"),

))

except AttributeError:

continue # No data

finally:

cls.free_sites(pointer[0],count )

return results

@staticmethod

def free_sites(array_pointer: CUser, count:int):

if not array_pointer:

return

lib.free_users(array_pointer, count)

users = User.create_random_users(10)

print(users)Conclusions

It’s over, I’m free, almost. This was one of the longest slogs I’ve had programming. It isn’t for the faint of heart, but it’s great when it’s done. This article gave you everything you need to start working with a process like this, and in the next article. I will show you some real world demos of this in action, as well as some of the higher level practical tips.

References

- CGO

- Ctypes

- Shared Libraries