The power of paths

scorch web theory low-level

Crossposted from https://schulichignite.com/blog/the-power-of-paths/

Table of contents

- Graphs, trees & nodes

- What are paths?

- Ways to encode locations

- Custom left-right format

- Cells

- Tic-Tac-Toe

- Code

- Other real-world examples

- Delimiters

- File paths

- Code

- Relative vs Absolute paths

- Document parsing

- Xpath & CSS

- URL parsing

- Lookups

- UUID/ULID

- Anchor/jump/hash links

- Path Finding

- Dead ends and scary characters

- Path invalidation

- Sanitizing and escaping

- Access Errors

- Variable encoding

- Query params

- Path params

- Multipath/pattern matching systems

- Regex

- State/attribute selectors

- Lookups & Partials

A path is a way to something. It’s how we go from what we know, and where we are, to what we want to know, and where we want to go. When we’re programming we often need to get information in some way. The question is how do we create a path to get that information that is:

- Easy to use

- Provides us the information we need

- Is efficient

- Can be reused

Whether it be a way to locate a file in a file system, or the way to locate an element on an HTML page, or an actual path between two locations on a map the solutions to these problems are often very similar.

Graphs, trees & nodes

Throughout the article I will use the terms graph and nodes. This is a computer science concept that comes up a lot. The basics are that a graph/tree is a collection of nodes that are linked together. Nodes can represent anything, but usually they represent an object (class instance). As a simple example imagine this dictionary in python ( I have added whitespace to make it easier to read):

users = {

"Kieran Wood":{

"age": 24,

"url":"https://schulichignite.com/authors/kieran-wood/",

"posts":[

{"It's caches all the way down":{

"url": "https://schulichignite.com/blog/its-caches-all-the-way-down/",

"tags":[

"optimization",

"web",

"scorch",

"theory",

"terminology"

]

}

}

]

},

"Spencer Fietz":{

"age": 24,

"url": "https://schulichignite.com/authors/spencer-fietz/",

"posts":[

{"Custom Web Fonts":{

"url": "https://schulichignite.com/blog/custom-webfonts/",

"tags":[

"css",

"web",

"scorch",

]

}

}

]

},

}This could be represented with the following tree. Nodes are the hexagons, and circles are attributes (url’s removed because they’re distracting):

flowchart TD

ZZ{{Users}} --> A & AA

A{{Kieran Wood}} --> b((24)) & c((url)) & d((posts))

d --> e((It's Caches All the Way down)) --> f((url)) & g((tags))

g --> h((optimization)) & i((web)) & j((scorch)) & k((theory)) & l((terminology))

AA{{Spencer Fietz}} --> BB((24)) & CC((url)) & DD((posts))

DD --> EE((Custom Web Fonts)) --> FF((url)) & GG((tags))

GG --> HH((css)) & II((web)) & JJ((scorch))

This is a useful visualization because each edge (arrow/line) tells you what the node is related to. So we know that Spencer and Kieran are both under the Users node, so we know that to find them we can start at the Users node and work our way down. This will come up later!

What are paths?

Paths come in many different forms, but essentially they all look to solve the problem of resource location. There is some sort of thing you want, and you need a way to specify where it is that allows you to access/store it. This can be used to specify where a file is/should be saved on your computer, to specifying a webpage a user wants, to even something like the moves made in a chess game.

Paths simply define the “path” to follow, the same way a sidewalk is a path you can use to get from one place to another, or a road. Essentially they are a set of instructions to get from point A to point B. Just like roads and sidewalks which can be concrete, dirt, gravel or any other material, paths can come in tons of different formats and require different ways to traverse them.

Ways to encode locations

There are many different standards that people use to encode locations. Encoding just means a way to take a set of information in one format, and convert it to another format. There are a ton of different formats for specifying locations, we will look at a few common types of data, and how to encode paths for them, as well as some generic encodings.

Custom left-right format

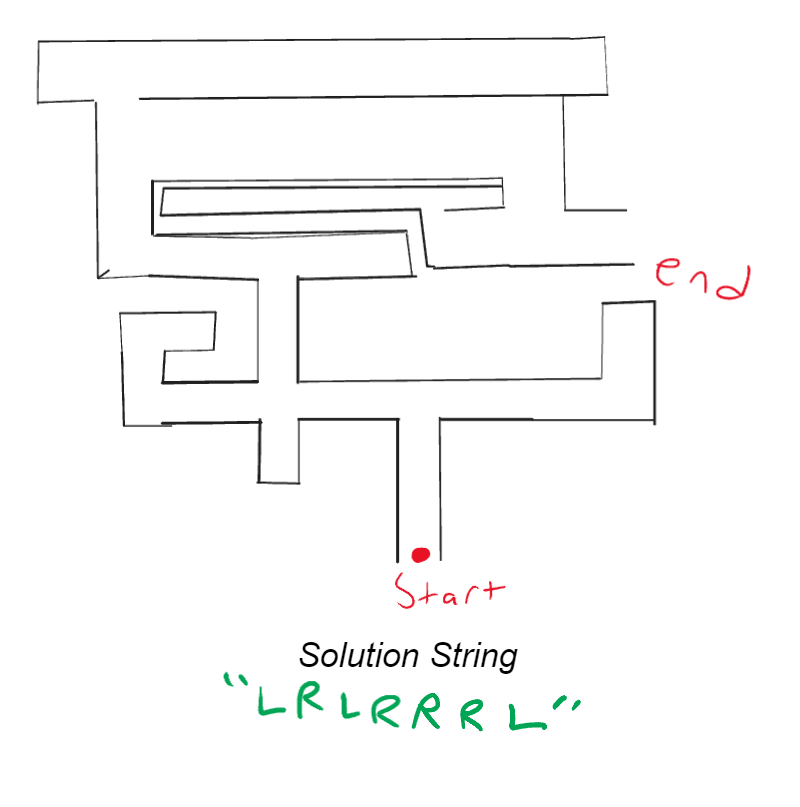

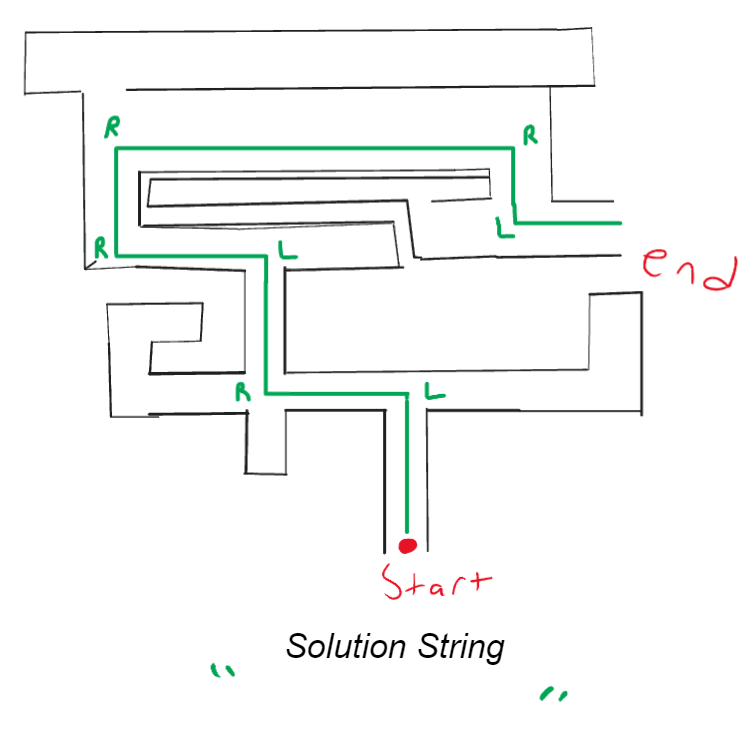

First, for a simple example let’s create an encoding for telling someone how to get out of a maze by telling them to turn left or right at a junction. We could encode this data by having “L” for left, then “R” for right and then string them together (i.e. “LRLRRRL” is left, right, left, right, right, right, left). As they move through the maze when they come up on a junction they take the leftmost letter in a string, go the direction it specifies, and then remove the letter. So starting with this:

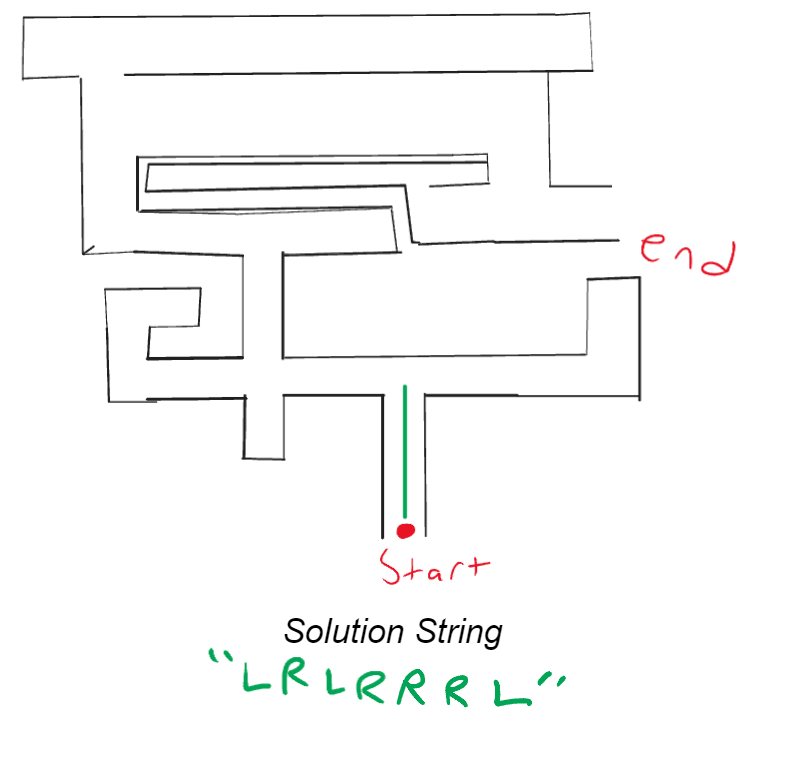

You can then start to walk the path by going straight until you come upon a junction:

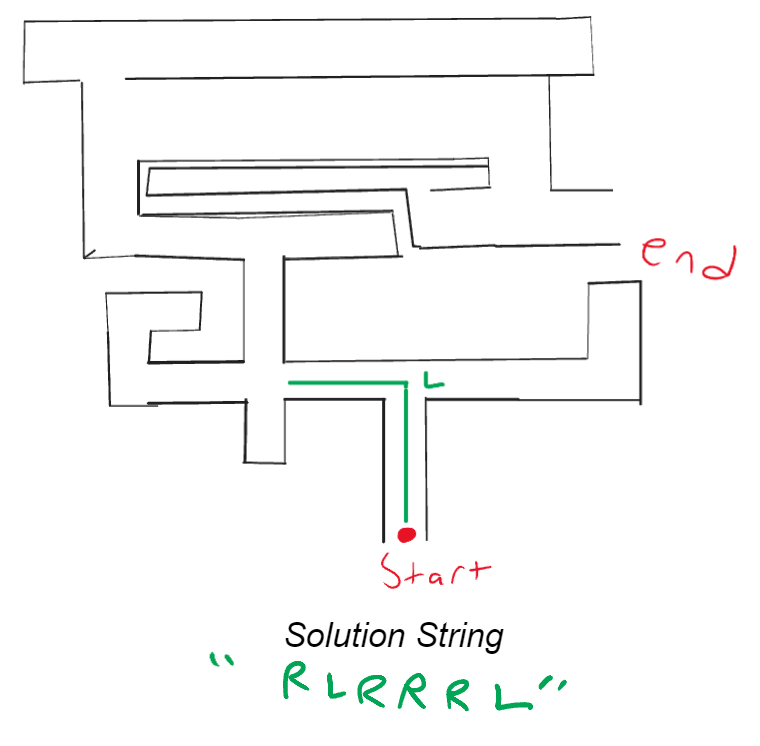

At this point you take the leftmost letter of the string, follow what direction it says, remove it from the string and then go straight until the next junction:

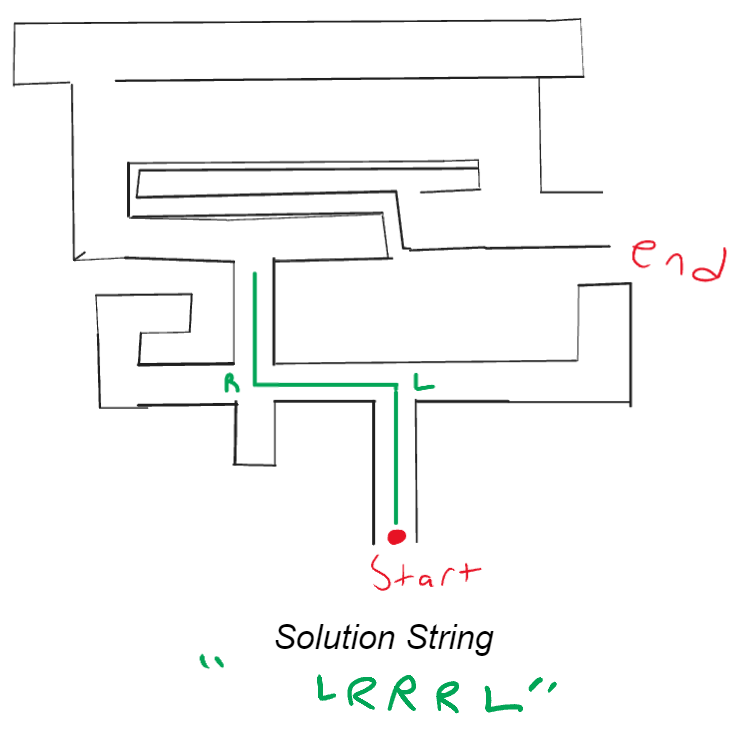

At this junction you then take the leftmost letter of the string, follow what direction it says, remove it from the string and then go straight until the next junction:

You then end with an empty string and the following solution:

This was our own custom system, but now let’s look at some common ways people use to do resource location.

Cells

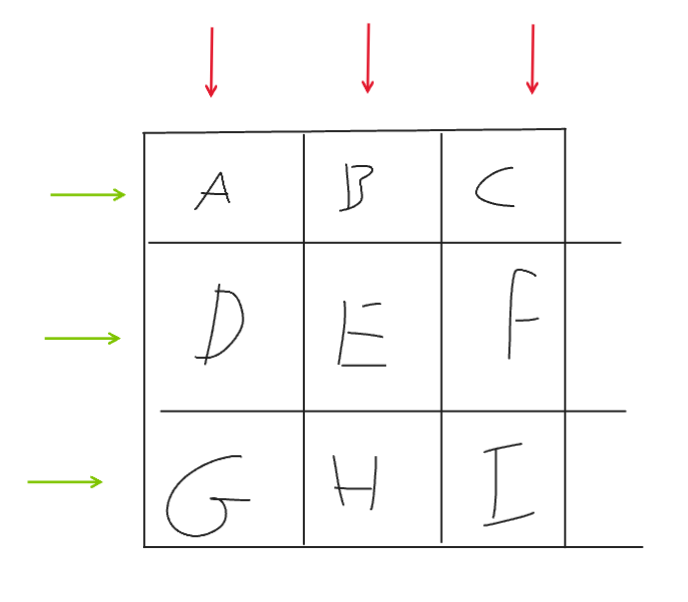

Cells are a common system used to specify a location in grid-like systems (chess, spreadsheets, Bingo, tables etc.). These encodings work by specifying locations in rows (green) and columns (red):

So the rows going from top to bottom would be A B C, D E F, and G H I, The columns are A D G, B E H, and C F I. With that knowledge let’s look at an example.

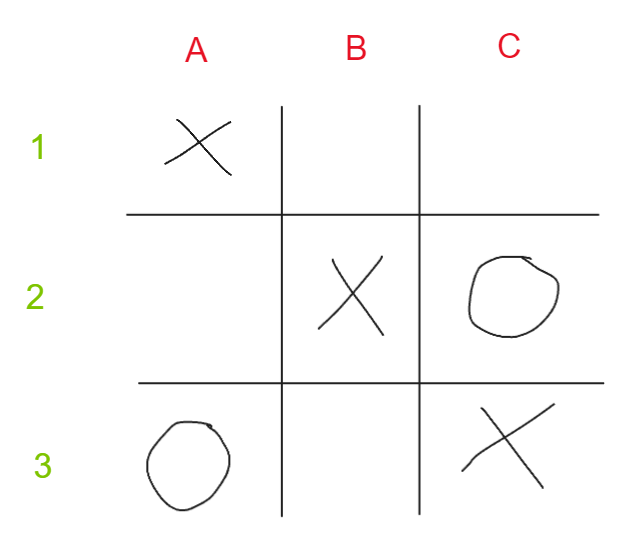

Tic-Tac-Toe

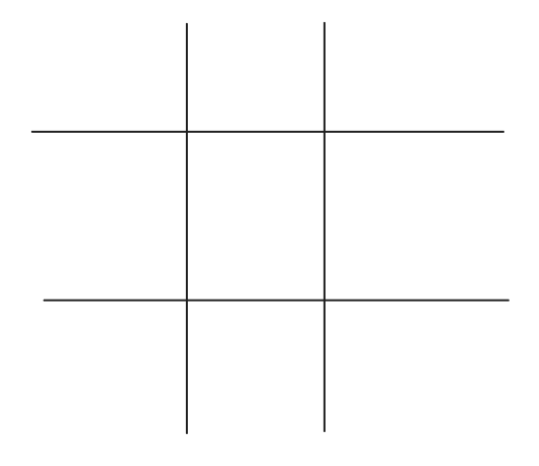

For example let’s use the game Tic-Tac-Toe, one player is “X” and another is “O”, each player is aiming to create a line of 3 of their assigned character. This can be horizontal, vertical, or diagonal. There are 9 squares in a grid to start with:

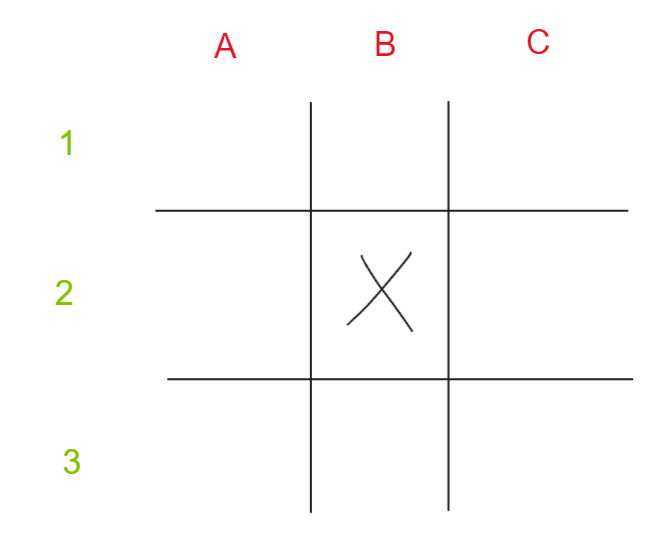

We can then add labels to the rows and columns to be able to label where each player puts their marks. In this case the X player puts their mark in the center, which is B2:

Now as the game goes on X eventually wins. We can now record this game by writing down how X won. In this case they won with a line at A1 B2 C3:

Code

We could put this example in code a few ways. One option would be to just take in a string of the moves, but this isn’t a great way of doing it because any number of formatting bugs have to be handled. Instead we could do this with some classes in python (if you’re unfamiliar look into dataclasses and type hints):

from dataclasses import dataclass

from typing import Literal, List

@dataclass

class Cell:

row: Literal[1, 2, 3] # Can be either a 1, 2 or 3

column: Literal["A", "B", "C"] # Can be either an "A", "B", or "C"

player: Literal["X", "O", None] = None # Which player has the space, defaults to None

@dataclass

class Board:

cells:List[Cell] # List of all the cells in the game

winner:Literal["X","O", None] = None # Which player has won, defaults to None

def player_move(self, player: Literal["X", "O"], column:Literal["A", "B", "C"], row:Literal[1, 2, 3]):

# Record a player's move

for cell in self.cells:

if cell.row == row and cell.column == column:

cell.player = player

return # Found cell

raise ValueError(f"Could not find cell {column}{row}")

# Testing

## 1. Setup cells for new game

cells:List[Cell] = []

for column in ["A","B","C"]:

for row in [1,2,3]:

cells.append(Cell(row, column))

## 2. Create new game

game:Board = Board(cells)

## 3. Register player moves

game.player_move("X", "B", 2)

game.player_move("O", "A", 3)

game.player_move("X", "A", 1)

game.player_move("O", "C", 2)

game.player_move("X", "C", 3)

## 4. Register Winner

game.winner = "X"

print(game) # Print the game recordOther real-world examples

There are tons of real-world examples of this sort of encoding being used, here are some examples:

- Algebraic Notation in Chess

- A1 & R1C1 Notation in Excel

- Sudoku

- Tielmapping (using location of pixels in an image to reuse textures)

- Coordinate systems (Cartesian Coordinates)

and there are many others!

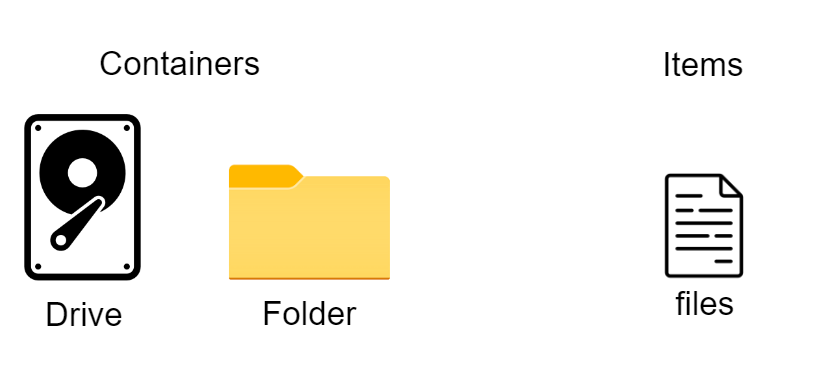

Delimiters

Delimiters are an incredibly useful encoding for paths. They are used in situations that have containers and items. Items are basically just whatever resource you are looking for (files, location in a map app etc.), containers are something that can contain other containers and/or items (folders, cities in a map app etc.). When we write a path we will specify the container that contains the items and delimit (seperate) them with some sort of indicator. This let’s our program know where to find exactly what we’re looking for.

File paths

For example on your computer file system you have drives & folders (containers), which hold files (items):

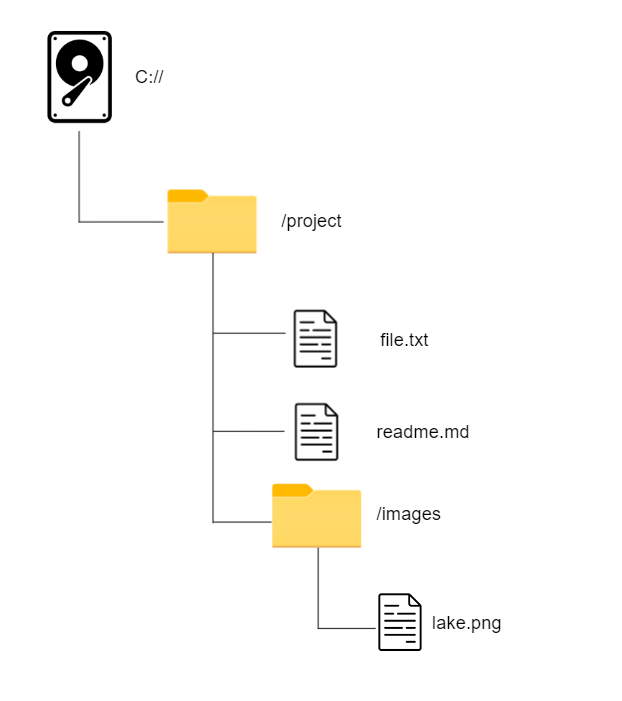

With this we could then have a drive on a computer with the following structure:

If we then wanted file.txt we could encode the path with C://project/file.txt. Effectively we start with C:// since that’s the drive that has the file we need, from there we basically use / to say “look inside here”. So if we wanted lake.png we would do C://project/images/lake.png as the path. In this case / is our delimiter, which means it’s what we use to make decisions about where to look inside.

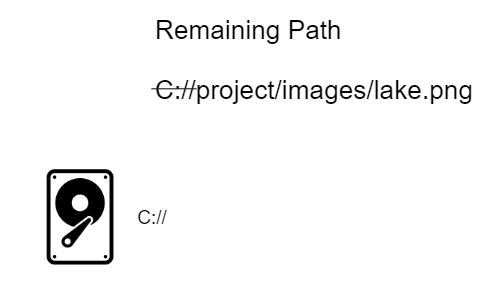

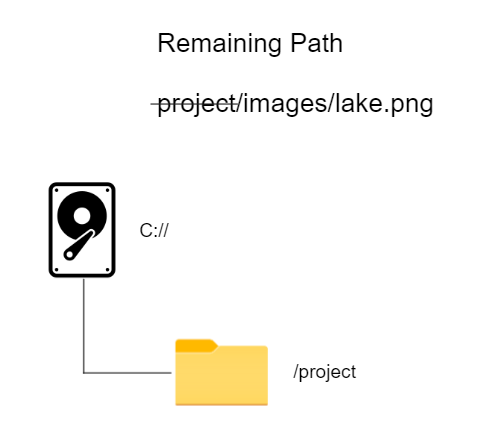

We can walkthrough the steps a program would take using the C://project/images/lake.png path. At the beginning we can just look for a drive, in our case C:// (as we go I will strikethrough the current step):

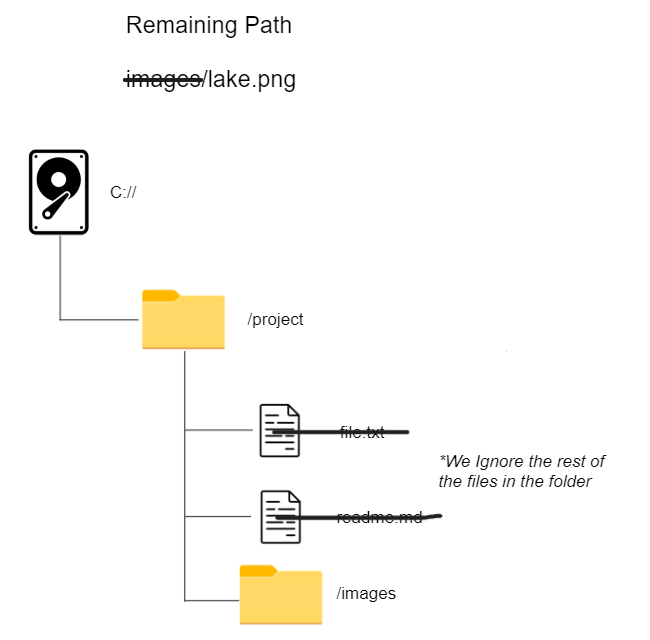

Now that we have the drive we can just read the remaining path from left to right until we encounter a delimiter (/), when we do we take the text to the left of the delimiter, find the folder, enter it and then look inside it using the rest of the path:

Now the same process again to go inside the images folder:

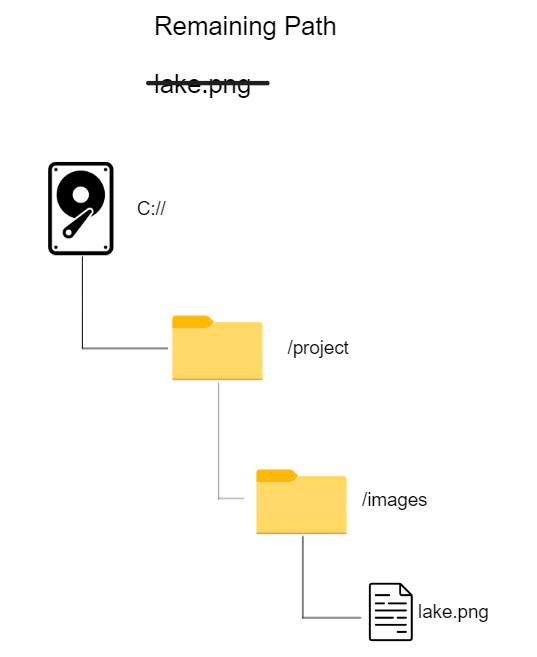

Then finally we have the file:

*In the real world windows uses \ linux and MacOS use / as path delimiters!

Code

This code shows a Very simple, long and buggy example of how you could make a “filesystem” in python. Since this example is long you can skip it by clicking here to go to the next section:

from __future__ import annotations # Allows type definitions to work properly

from string import ascii_uppercase # All uppercase letters in a list

from dataclasses import dataclass # Used to create classes faster

from typing import Literal, List, Union # Used to type class attributes faster

# Forces a value to be an uppercase letter

UPPERCASE_LETTERS = Literal[

'A', 'B', 'C', 'D', 'E', 'F', 'G', 'H', 'I',

'J', 'K', 'L', 'M', 'N', 'O', 'P', 'Q', 'R',

'S', 'T', 'U', 'V', 'W', 'X', 'Y', 'Z'

]

@dataclass

class File:

filename:str

@dataclass

class Folder:

name: str

contents: Union[List[Union[Folder, File]], None] = None # The contents of Folder

@dataclass

class Drive:

letter: UPPERCASE_LETTERS # Forces a value to be an uppercase letter

contents: Union[List[Union[Folder, File]], None] = None # The contents of drive

def find_folder(container:Union[Drive, Folder], folder_name:str) -> Folder:

# Finds a folder in a specified container

for item in container.contents:

if type(item) == Folder:

if item.name == folder_name:

return item

raise ValueError(f"Could not find folder {folder_name} in {container}")

def find_file(container:Union[Drive, Folder], file_name:str) -> File:

# Finds a file in a specified container

print(f"Checking if {container.name} has file {file_name}")

for item in container.contents:

if type(item) == File:

if item.filename == file_name:

return item

raise ValueError(f"Could not find file {file_name} in {container}")

def get_file(path: str, drives:List[Drive]):

# Get's a file using a provided path

if not path[0] in ascii_uppercase:

raise ValueError("Incorrect path provided")

# Find correct drive

correct_drive = None

for drive in drives:

if path[0].upper() == drive.letter:

correct_drive = drive

break # End loop

if not correct_drive: # No drive with the letter was found

raise ValueError(f"No drive with leter {path[0]} found")

# Manipulate the path variable

path = path[4:] # Remove drive information

## Assign variables for the loop

filename = path.split("/")[-1] # Get just the filename

folders = path.split("/")[:-1] # Get just the folders as a list of str's

current_folder = find_folder(correct_drive, folders[0])

folders.pop(0) # Remove first folder since it's the current_folder

correct_file = None

if not folders: # If the file is in the current directory/drive

correct_file = find_file(current_folder, filename)

# Loop over each folder to find the file

for folder in folders:

# Assign the current folder to the current piece of the path

current_folder = find_folder(current_folder, folder)

try:

print(f"Checking {folder}")

correct_file = find_file(current_folder, filename)

break

except ValueError:

print(current_folder)

print(correct_file)

# Testing

## Create files and folders

project_folder = Folder("project", [

File("file.txt"),

File("readme.md"),

Folder("images", [

File("lake.png")

])

])

## Create drive

c = Drive("C", [project_folder])

# Test looking for the file

print(get_file("C://project/images/lake.png", [c]))Relative vs Absolute paths

Up until this point we have been using absolute paths when talking about files. Absolute paths give you exactly where things are. It tells you which drive to look in, and exactly which folders. The advantage with this is that you can find what you’re looking for from anywhere on the computer. But they can also be long and unruly to deal with. For example here is the link to this webpage on my computer C:\Users\Kieran\Desktop\development\ignite\website\content\blog\the power of paths.md.

But what if I currently have the website folder open? Why do I have to go back all the way and parse all of C:\Users\Kieran\Desktop\development? I could just skip that whole part. Relative paths do exactly that. When you run a script, or a file from a terminal your terminal already has a location open in order to read the file. Relative paths use your current working directory (cwd, or the folder you’re in currenly) to make paths easier to work with. This is handy because it’s shorter, and also it helps avoid problems with if you rename a directory. If I were to rename the project from /website to ignite-site the entire absolute path would break, but if I assume I’m already in that folder when I’m running the command, it doesn’t matter!

Relative paths have a couple of special characters they use:

.This is your current folder you are in (cwd)..This means “go up a directory”. So if you have an absolute pathC://folder-1/folder-2/python.exe, and you are inside/folder-2, you can use..as a relative path to/folder-1

Document parsing

Another example of delimiters that is common is in document parsing. Microsot word documents, HTML documents (like this page), slideshow presentation systems etc. all use delimiters to build document trees. If you are familiar with classes essentially what happens is as the source code is read a bunch of instances/objects are generated, you can then access those objects/instances with languages to manipulate them. The most common form of this is HTML being manipulated with Javascript.

If you are unfamiliar with HTML or Javascript you should take our scorch course to learn more, but the basics are with HTML you create elements, these elements all have a few parts:

- Start tag; Indicates where an element starts (and what tagname or type of element it is)

- End tag; Indicates where an element ends

- Attributes (optional); Additional configuration information for the element (i.e. a link to a webpage for an anchor tag)

- Inner Content (optional); Text and other HTML that can be placed inside elements

The format is:

<tagname attribute="value">

innercontent

</tagname>So for example here is a div tag (generic container), with a heading 2 tag (large text), and an anchor link (link to a page):

<div>

<h2>Hello World!</h2>

<a href="https://schulichignite.com">Link to ignite!</a>

</div>With javascript we could then access the h2 element using document.getElementsByTagName(). This returns an array of elements, and in our case we want the first one in the document, so we access the 0th index:

console.log(document.getElementsByTagName("h2")[0]) // Logs the elementUnder the hood the browser is reading the HTML we provide, and creating a tree of Element’s (objects). These Element’s have a ton of attributes and methods associated with them, but the most important for us are the children and parent attributes. Essentially as the browser encounters an Element it creates a new object, then it will attach any Elements found inside the Element to the children attribute, and then inside the new Element attach the outer Element as a parent. So with the following HTML:

<body>

<div>

<h2>Hello <strong>World!</strong></h2>

<a href="https://schulichignite.com">Link to ignite!</a>

</div>

<div>

<h3>Hello <em>There!</em></h3>

<p>Lorem Ipsum dolor</p>

</div>

</body>We would have something like this:

flowchart TD

ZZ{{Body}} --children--> A & AA

A{{div}} --children--> b{{h2}} & c{{a}}

b --children-->d{{strong}}

AA{{div}} --children--> BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}}

BB --children-->DD{{em}}

We could then add in the parent relations:

flowchart TD

ZZ{{Body}} --children--> A & AA

A & AA --parent--> ZZ{{Body}}

A{{div}} --children--> b{{h2}} & c{{a}}

b --children-->d{{strong}}

b{{h2}} & c{{a}}--parent--> A{{div}}

d{{strong}} --parent-->b

AA{{div}} --children--> BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}}

BB --children-->DD{{em}}

BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}} --parent--> AA{{div}}

DD{{em}}--parent--> BB

Then under the hood there is an extra node created called document:

flowchart TD

QQ{{Document}} --children-->ZZ

ZZ --Parent-->QQ

ZZ{{Body}} --children--> A & AA

A & AA --parent--> ZZ{{Body}}

A{{div}} --children--> b{{h2}} & c{{a}}

b --children-->d{{strong}}

b{{h2}} & c{{a}}--parent--> A{{div}}

d{{strong}} --parent-->b

AA{{div}} --children--> BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}}

BB --children-->DD{{em}}

BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}} --parent--> AA{{div}}

DD{{em}}--parent--> BB

So now to search for the h2 tag like before we just start at the document node, and then search the children of each node in the tree one at a time to find what we need. Since we’re looking for all h2’s we can create an empty array, and append to it as we find Element‘s. This might look something like this in steps:

flowchart TD

AA{{div}} & A{{div}}

QQ{{Document}} --1. Check if an h2-->ZZ{{Body}}

ZZ{{Body}} --2. Check if an h2--> A & AA

A{{div}} --3. Check if an h2 --> b{{h2}} & c{{a}}

AA{{div}} --3. Check if an h2 --> BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}}

At step 3 since we found an h2 we can append that Element to our result list and continue searching the rest of the Element’s:

flowchart TD

AA{{div}} & A{{div}}

QQ{{Document}} --1. Check if an h2-->ZZ{{Body}}

ZZ{{Body}} --2. Check if an h2--> A & AA

A{{div}} --3. Check if an h2 --> b{{h2}} & c{{a}}

AA{{div}} --3. Check if an h2 --> BB{{h3}} & CC{{p}}

b --4. Check if h2--> d{{strong}}

BB --4. Check if h2-->DD{{em}}

Now that there are no more Element’s to check we return the result list, which has only the one element!

Xpath & CSS

CSS is another language used in web development to style webpages. It uses a selector system to find elements on a page to effect. This is another form of path encoding, it is too complex to go into here, but you can find a reference guide here. We will just cover some basics. For example we could with the following HTML:

<div>

<h2>Hello World!</h2>

<a href="https://schulichignite.com">Link to ignite!</a>

</div>Select any anchor link (a) inside a div and make it red:

div a{

color: red;

}or even select just links to https://schulichginite.com and make them orange, while making every other anchor tag in a div red:

div a{

color: red;

}

a[href="https://schulichignite.com"]{

color: orange;

}CSS supports a bunch of fancy queries like only the first element of a type inside another element, or only every odd row in a table etc.

CSS is not the only way to locate elements in a document though. There is another standard called Xpath, which will look familiar. It is a way to specify looking up HTML elements in a file-path-like syntax. This is used in many systems including automation frameworks like selenium. Actually HTML is just a subset of elements for a language called XML, which is where the X in Xpath comes from! For example if we have the HTML:

<div>

<h2>Hello World!</h2>

<a href="https://schulichignite.com">Link to ignite!</a>

</div>and we wanted to access the h2 element, we could do:

/div/h2 or ./div/h2 or div/h2

This is useful for more advanced queries like state queries (select elements based on attributes, text inside them etc.), multi-option queries (if element matches A or B paths), and location-based lookups (only the 3rd element of a certain type in the document). It can be used in javascript with evaluate(), but there are better ways to do this in javascript. It’s mostly useful for languages that don’t run in the browser like python where you can use it to query a system that makes sense out of HTML files like lxml, or in cases where HTML isn’t the only type of XML-like file you’re going to be working with!

You can play around with Xpath using utilities like xpather.

URL parsing

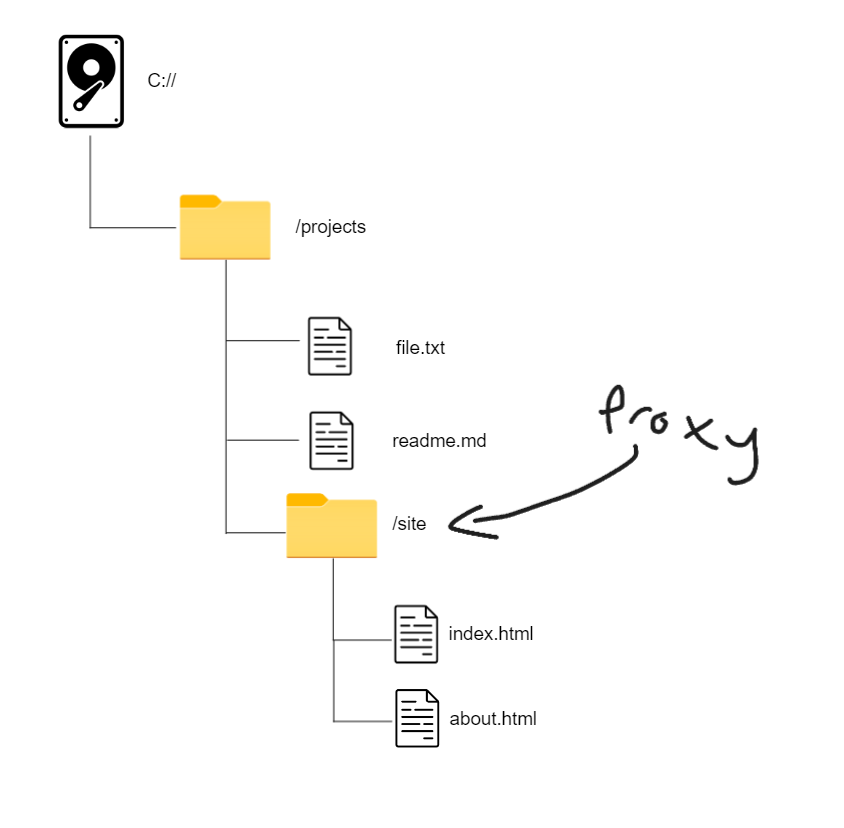

URL’s are what you use to access websites. For examplle this page is on https://schulichignite.com/blog/the-power-of-paths and this looks pretty familiar! It’s very similar to file paths, and in the old days it actually was. Old servers used to just proxy a folder. What that means is you would have some domain like example.com, that domain would then act like a current working directory from which people would then specify the HTML file they wanted to see! So if we had something like this, where the proxy is on /site:

Then when users go to example.com they would get index.html (reserved name for historical purposes), then if they went to example.com/about they would get about.html!

Most webservers do fancier things these days. For example flask will allow you to write templates using jinja. This is basically a fancy way of generating HTML from a file on-demand, which let’s you do things like update the page with the weather for the day. So a file like this:

<h1>The weather today is:{{todays_temperature}} degrees celcius</h1>When a user comes to the URL, let’s say weather.com/today then it will load the file (today.jinja), and then return the content back to the user as if it were a normal HTML file!

Lookups

In systems that have guarenteed unique values you can often specify a path to something by a value. For example let’s say we have a database of users, and every user gets assigned an ID. It starts at 0, and is increased by 1 every time. This could then be used to lookup the user in a database since the ID is right there! This can be implemented with something as simple as a function that takes in an ID to lookup, and then goes through your resources to find the one with the ID, and return it.

UUID/ULID

Adding an increasing single number seems like a good way to do lookups, but it can cause problems. For an example imagine you’re creating files with the ID numbers (1.json,2.json etc.), and then you restart your app and the counter resets. You might end up overriding the values. Not to mention sometimes you might want to identify things uniquely in a way that isn’t guessable. For example a screenshot image hosting service, don’t want people to just go through each number and harvest personal data (ahem… lightshot).

UUID’s (Universally Unique IDentifier) is a system that generates a very hard to guess, and unique ID for exactly these sorts of situations. Another option for this is UULD’s (Universally Unique Lexicographically Sortable Identifier), this works the same as UUID’s except they allow you to check which ID was created before another. This is useful if you have a lot of data, and need to sort by time created (like a ecommerce shop where you have new products coming out all the time). This also makes it more efficient for sorting, and determining if an item exists, if you can tell for example that the ID a user is requesting does not exist within a range, then you know the ID is invalid!

Anchor/jump/hash links

In URL’s you will often have Anchor/jump/hash links. These are URL’s that will include a # at the end with an indicator. This indicator can be used to find locations that are specified by unique identifiers. For example in HTML if you add an ID to an element then there should only be 1 element with that ID (making it unique). Here is an example of the syntax used to create a table of contents:

<style>

div{

height: 80vh; /*Make divs large so you can see the page move*/

}

</style>

<div>

<h3>Table of contents</h3>

<ul>

<li><a href="#section-1">Section 1</a></li>

<li><a href="#section-2">Section 2</a></li>

<li><a href="#section-3">Section 3</a></li>

</ul>

</div>

<div id="section-1" style="background:red; color:white;">

Sunt et nisi aliquip ut consectetur laborum minim officia eu. Anim consequat sunt excepteur Lorem officia minim commodo ex fugiat culpa ipsum occaecat aute officia. Sint fugiat sit officia ullamco tempor tempor. Voluptate pariatur excepteur ex mollit irure dolore consectetur non aute veniam exercitation. Ut cillum proident enim mollit esse pariatur id aute reprehenderit. Aute cupidatat tempor quis proident commodo quis dolore non.

</div>

<div id="section-2" style="background:blue; color:white;">

Sunt et nisi aliquip ut consectetur laborum minim officia eu. Anim consequat sunt excepteur Lorem officia minim commodo ex fugiat culpa ipsum occaecat aute officia. Sint fugiat sit officia ullamco tempor tempor. Voluptate pariatur excepteur ex mollit irure dolore consectetur non aute veniam exercitation. Ut cillum proident enim mollit esse pariatur id aute reprehenderit. Aute cupidatat tempor quis proident commodo quis dolore non.

</div>

<div id="section-3" style="background:orange; color:white;">

Sunt et nisi aliquip ut consectetur laborum minim officia eu. Anim consequat sunt excepteur Lorem officia minim commodo ex fugiat culpa ipsum occaecat aute officia. Sint fugiat sit officia ullamco tempor tempor. Voluptate pariatur excepteur ex mollit irure dolore consectetur non aute veniam exercitation. Ut cillum proident enim mollit esse pariatur id aute reprehenderit. Aute cupidatat tempor quis proident commodo quis dolore non.

</div>Clicking any of the anchor tags will append #section-<number> to the end of the URL, which will trigger the browser to go to the element that has that ID. You can also work with these types of links directly in javascript using hash. This method is used for a ton of things including tables of content, and even to link to a specific clide in web-based slideshow systems like webslides.

Path Finding

While all these encoding formats for paths are great one question you might have is how you can actually find paths. There are tons of path finding algorithms for different use cases. They are a bit too complicated to look at in this article but here are some to look into:

Dead ends and scary characters

Not all paths go somewhere, or somewhere valid. There are several common types of bugs that occur with paths (and encodings in general), that you should be aware of as well as the solutions to these bugs. This is not an exhaustive list, but it should give you enough to solve the most common problems.

Path invalidation

Sometimes when you’re given a path you will find out it’s invalid in some way (folder doesn’t exist or is misspelled). In these dead end cases there’s not much you can do besides request the user to change the path to a correct one.

Sanitizing and escaping

When writing paths (especially delimiter paths) there are reserved symbols. For example / is reserved to indicate a folder, but what if a folder has a / in the name? In these cases where there are reserved characters that mean something special, you need to sanitize and/or escape the values. Sanitization is basically a process of finding any characters that should not be there and blacklisting them. This can be done by raising an error if they’re found in the wrong spot, or by stripping them from the path when they’re not supposed to be there.

Escaping on the other hand still allows you to “use” those characters, but write them in a way that guarentees they are treated as text instead of as whatever they’re used for. For example with URL’s you cannot include spaces, instead you use a % and then the hex value in ascii. So for something like https://example.com/my page it would become https://example.com/my%20page instead! Escaping would be done as a step just before whatever you’re using to process the path.

Access Errors

Sometimes the path can be completely valid, but the user doesn’t have access to the resource. On the web this will result in a HTTP 403 error code, or on a computer this will be an access error in the filesystem. The only thing you can do in this case is ask the user to authenticate, but if their account doesn’t have access, then they can’t access te resource!

Variable encoding

You can also often include data in your paths that can be used to help the processing. This can be to help you locate something inside a resource (a portion of a file), or to pass information to a resource when you access it (values like your username on a webpage).

For example with URL’s in the browser there are three systems where you can pass data to the system reading the path called anchor/jump/hash links (see above), path parameters and query parameters. This can be useful to have someone for example go to another section in a document, in fact if you clicked any of the links in the previous sentence they are all anchor links that take you to different portions of the same resource (this page).

Query params

Query Parameters are values are included after the url with ? and key-value pairs for example:

weather.com/today?city=calgaryMultiple parameters

weather.com/today?city=calgary&measurements=celciusThese are used to provide data to the page reading them. One example is that this is used on contact pages to pre-fill infromation. For example if you have a button on a product page to contact support for help about buying a particular product you might include /contact?product=product_name where product_name is the name of the product and then on the page you read that value into the form and pre-fill the subject line!

Path params

Path Parameters are values that are included in the main URL. So for example weather.com/calgary the API will define

weather.com/{city} The /calgary in weather.com/calgary is a variable called city

Multiple Parameters

weather.com/{city}/{measurement}

weather.com/calgary/celciusI used {} here to indicate a variable, but some systems use <>, like /<city>. These are very common for filters. On this site for example you can filter by tag if you go to https://schulichignite.com/tags/{tag} (i.e. https://schulichignite.com/tags/web)

Multipath/pattern matching systems

Sometimes you don’t want a path to just 1 thing. For example you might want to look for all files that have a certain phrase in them, or that have a certain set of numbers. One example might be a folder with a bunch of text files that all have the year they were created in the name:

└── 📁/reports

├── 📃2023.txt

├── 📃2022.txt

├── 📃2021.txt

├── 📃2020.txt

├── 📃2019.txt

├── 📃2018.txt

├── 📃2017.txt

├── 📃2016.txt

├── 📃2015.txt

├── 📃2014.txt

├── 📃2013.txt

├── 📃2012.txt

├── 📃2011.txt

├── 📃2010.txt

├── 📃2009.txt

├── 📃2008.txt

├── 📃2007.txt

├── 📃2006.txt

├── 📃2005.txt

├── 📃2004.txt

└── 📃2003.txtYou might want some way to be able to specify a pattern that the data takes, and get a set of paths that match that pattern. For example all files between 2004-2010, or all files that have a .txt extension.

Regex

Regex (regular expressions) is a language for pattern matching. It let’s you define patterns that it will then match for and return the results (guide here). Regex is way to complicated to cover in this article, but essentially the way it works is you define a string, that string contains the patterns you’re looking for. Here is a cheat sheet to show off what all the symbols mean.

Here are a couple of common use cases that are easy. For all of these cases we define a list of strings we wanna search through, then we define our pattern (the r in front of a string means to treat things like \n as the text \n not a newline like a normal string), and then we create a list of matching files using the pattern and the re.search function (re is the regex module in python).

Finding all files with .txt:

import re # Lets you use regex in python

file_names = [

'2003.txt', '2004.txt', '2005.txt', '2006.txt',

'2007.txt', '2008.txt', '2009.txt', '2010.txt',

'2011.txt', '2012.txt', '2013.txt', '2014.txt',

'2015.txt', '2016.txt', '2017.txt', '2018.txt',

'2019.txt', '2020.txt', '2021.txt', '2022.txt',

'2023.txt'

]

pattern = r".*\.txt"

matching_files = [file for file in file_names if re.search(pattern, file)]

print(matching_files)Find all files between 2004-2010 in python:

import re # Lets you use regex in python

file_names = [

'2003.txt', '2004.txt', '2005.txt', '2006.txt',

'2007.txt', '2008.txt', '2009.txt', '2010.txt',

'2011.txt', '2012.txt', '2013.txt', '2014.txt',

'2015.txt', '2016.txt', '2017.txt', '2018.txt',

'2019.txt', '2020.txt', '2021.txt', '2022.txt',

'2023.txt'

]

pattern = r"(200[4-9]|2010)\.txt"

matching_files = [file for file in file_names if re.search(pattern, file)]

print(matching_files)State/attribute selectors

When parsing documents (especially on the web) we can find another example of variable encoding called state/attribute selectors. Most places call these attribute selectors (since that’s the official name), so I will just call them attribute selectors from here on out. Attribute selectors allow you to find elements in a document based on the attributes/state of the element. Ocassionally this is guarenteed to only find 1 result (document.getElementByID()), but most selectors will find any elements that match the provided criteria (as explained here). For this we will use CSS to find any element that has a link to schulichignite.com and color it orange:

a[href^="https://schulichignite.com"]{

color:orange;

}in this case the ^ indicates that this is the string that should be at the start of the href, but there are other options to do this sort of pattern matching, details can be found here.

There are other types of selectors we can use called pseudo classes which allow us to have conditional CSS based on the element state. These are in the format of:

selector:pseudo-class{

/*CSS rules here*/

}Where selector is a normal CSS selector you would use. For example changing the color of text only when a user hovers over it:

a:hover{

color:blue;

}We can also select according to the state of an element relative to the document. The most common example is “tiger striping” a table. As you can see on this page, odd rows are coloured differently in the html:

| column | column | column |

|---|---|---|

| row | row | row |

| row | row | row |

| row | row | row |

The HTML for the above table is:

<table>

<thead>

<tr>

<th>column</th>

<th>column</th>

<th>column</th>

</tr>

</thead>

<tbody>

<tr>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

</tr>

<tr>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

<td>row</td>

</tr>

</tbody>

</table>We then use the CSS rule:

tr:nth-child(odd) {

background-color: #fffbea;

}This says that if the currentt row is an odd number as a child of the tbody then change it’s colour.

Lookups & Partials

Earlier in the lookups section I mentioned that lookups require guarenteed uniqueness. This is true if you are looking for a result, if you are fine with multiple items (like in searches), then you might not need the uniquenes constraint. For example if you are building a search system for movies and someone enters a search term like "inside", you may want to return all movies that have inside in the title (which is more than 1). In these cases your search term would be used to locate multiple resources, but you would still want a unique identifier for each movie so you can find the information about the 1 movie the person is looking for.