HHTTPPP; Parsing HTTP requests and responses

python scorch web theory

Crossposted from https://schulichignite.com/blog/hhttpp/parsing-requests-responses/

Table of contents

Now that we have our basic HTTP structure we need a way to read actual http requests/responses. Currently we have hardcoded everything, so today we will focus on creating everything we need for steps 2-4:

- Recieve plaintext request

- Parse the plaintext into a

Requestobject - Process the

Requestobject and generate aReponseobject - Generate a plaintext response from the

Responseobject

Terms & Concepts

To start there are some terms we need to understand. Here’s what we need to know about, and what we’re going to cover in more detail later.

| Term | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Parser | A piece of code that can read data in one format (usually plain text) and parse them into another format (object, different text format etc.) | A fast HTTP parser in python (also anything that works with HTTP will have some sort of parser) |

| Data Sanitization | Removing parts of an input that might cause undesirable behaviour | Cleaning text that comes in from a comment that could be interpreted as HTML so it doesn’t render as HTML when people visit the comments later |

What is regex?

Regex is a pattern matching language. It let’s you define patterns of text that it will then return the matches for. So if you wanted to extract all the numbers from some text you can define a regex pattern. The patterns are called regex expressions, and are just plain text. For example all of the below are regex patterns:

"[A-z]" # Match any single uppercase or lowercase character

"[a-z]" # Match any single lowercase character

"[aef]" # Match any single a, e or f

"\d" # Match any single digit (0-9)Regex will usually parsed in python using the re module (but we will also use glob), and will create Match objects. These Match objects contain each match for the pattern you define. There are lots of different ways to use regex, but we will use 2 ways, globbing and capture groups.

Capture groups is essentially the idea that we define a set of “groups”, and for each Match in the pattern there will be “groups” of text matched. For example we might read the first line of a HTTP request we will want different groups for the method, slug and http version. To create groups you put a sub-expression into parenthesis. For example to capture a single letter, and a single digit into separate groups you do ([A-z])(\d). This will find any letter then digit, so for example with the string "a1,b5,dt,r7" would have 3 matches a1, b5 and r7 each with 2 groups:

a1: Group 1 isa, group 2 is1b5: Group 1 isb, group 2 is5r7: Group 1 isr, group 2 is7

We will cover globbing in the next section, it is a bit easier to do and is used to get a list of files.There is not enough time to cover regex fully, but for each set of regex we will use there will be an image explaining each portion of the expression. You can check the more resources section for a general introduction to regex thatgoes into more details.

Why?

Regex is great for more complex patterns you need to locate. There are a few cases, but I want to give a comparisson to an alternative first. Iterative searching is where you go line-by-line and create some code that looks for your pattern manually. For example below we have the iterative code for collecting just the words that come before “apple” in a sentence

test_input = """blah blah apple blah blah

blah, blah blah blah apple apple

blah apple

apple

blah blah blah blah

"""

def get_words_before_apple(text:str) -> str:

result = []

for line in test_input.split("\n"):

if "apple" in line:

start = line.index("apple")

result.append(line[:start:]) # Cutt off at start of apple

else:

result.append(line)

return "\n".join(result)

get_words_before_apple(test_input)2 points about this code:

- There are a ton of whitespace bugs, along with other logical errors

- A regular expression would be much smaller, and likely easier to understand (

^(.*)apple.*)

That being said keep in mind that pattern matching in general is not always super simple (writeup on this case, another relevant article), and most of the code, and regex you see initially had bugs when I wrote it. Any pattern matching is a great time to write tests, because trying to find ways to break your patterns leads you to improving them!

Regex

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Universal accross languages | Used in tons of applications beyond just in programming languages (file+folder organization, searching etc.) |

| Syntax stays the same, so other people can help debug if they’re familiar with it | large learning curve initially |

| It is often faster than the iterative approach because the language will optimize the module/package for regex | The more clever the pattern, usually the more difficult it is to understand |

| There are tons of tools to help you write regex | You often need tools to understand a regex pattern |

When to use

You can use regex whenever, but the ideal situation is when you have complex patterns that would take a lot of effort to implement with itterative approaches. For example only the uppercase letters that occur between the worlds apple and strawberry ^.*apple(.*)strawberry.*$.

Additionally it can be used for more than just pattern matching in programs, regex can be a useful skill to learn for:

- Searching with grep

- Organizing files + folders

- Searching & replacing in text editing applications (like vs code)

Iterative Approach

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| No special pattern-matching language knowledge required | Often slower than regex because regex modules are often highly optimized |

| For super simple patterns it’s often easier to reason about | Complex patterns become very hard to reason about often |

This works fine in python, but in lots of other languages you tend to itterate per letter. Regardless of which you choose to go with in your code I will cover options for both in the rest of the article.

Getting file lists

There are two more attributes we have added to the Server class, file_list and urls. file_list is a list of all the paths of files in Server.proxy_directory, and URL’s are going to be the URL’s that correspond to each file. The code for this can be found in Server.__post_init__(), and in this section we will describe how we generate Server.file_list.

We are going to use the glob module to get a list of files. This lets us define patterns similar to regex, but it’s specifically built for files. Since this is less applicable the basics are that * means replace with anything. So in our case to get every single file in a folder we can do glob.glob("*.*"). This is great, but what about if we have subdirectories (i.e. /js/file.js)? Now we need a fancier pattern.

The easiest way to do this is following the pattern <folder>/**/*, this says all files in all folders. We then pass the recursive flag and it will find everything glob.glob("<folder>/**/*, recursive=True). For performance reasons we are going to use glob.iglob() (works the same), and we will replace <folder> with the absolute path to the proxy_directory we set on our server object.

Putting it all together here is the basic idea:

class Server:

... # More code

def __post_init__(self):

proxy_dir = os.path.abspath(self.proxy_directory) # Making path absolute makes this easier

for file in glob.iglob(os.path.join(proxy_dir, '**',"*.*"), recursive=True):

self.file_list.append(os.path.join(proxy_dir, file))In the actual code I did the second part with a list comprehension:

class Server:

... # More code

def __post_init__(self):

proxy_dir = os.path.abspath(self.proxy_directory)

self.file_list = [

f"{os.path.join(proxy_dir, file)}"

for file in glob.iglob(os.path.join(proxy_dir, '**',"*.*"), recursive=True)

]Creating URL’s from file list

Now that we have the files, we want to make sure that we can match URL’s when they come in. For example if we recieve a GET request with /about as the slug we need to know what file to grab. In our case the only two extra rules we will have are:

- That HTML files will get their regular filenames, and their file with no extensions as valid URL’s. For example

/aboutand/about.htmlwill point to the same file. To do this we need a dictionary mapping of these URL’s to the files to be able to find it. /is an alias forindex.html(this is just the norm in webdev)

So for example some simplified code might look like this:

proxy_directory = "/site"

files = ["/site/about.html", "/site/js/main.js", "/site/index.html"]

urls = dict()

for file in files:

if file.endswith("index.html"): # Homepage

urls["/"] = file

urls["/index.html"] = file

elif file.endswith(".html"): # HTML files

urls[file.replace(proxy_directory, "")] = file # filename (i.e. /about.html)

urls[file.replace(proxy_directory, "")[:-5:]] = file # remove extension (i.e. /about)

else: # Non-html files

urls[file.replace(proxy_directory, "")] = file

print(urls) # {'/about.html': '/site/about.html', '/about': '/site/about.html', '/js/main.js': '/site/js/main.js', '/': '/site/index.html', '/index.html': '/site/index.html'}The actual implementation can be found in Server.__post_init__().

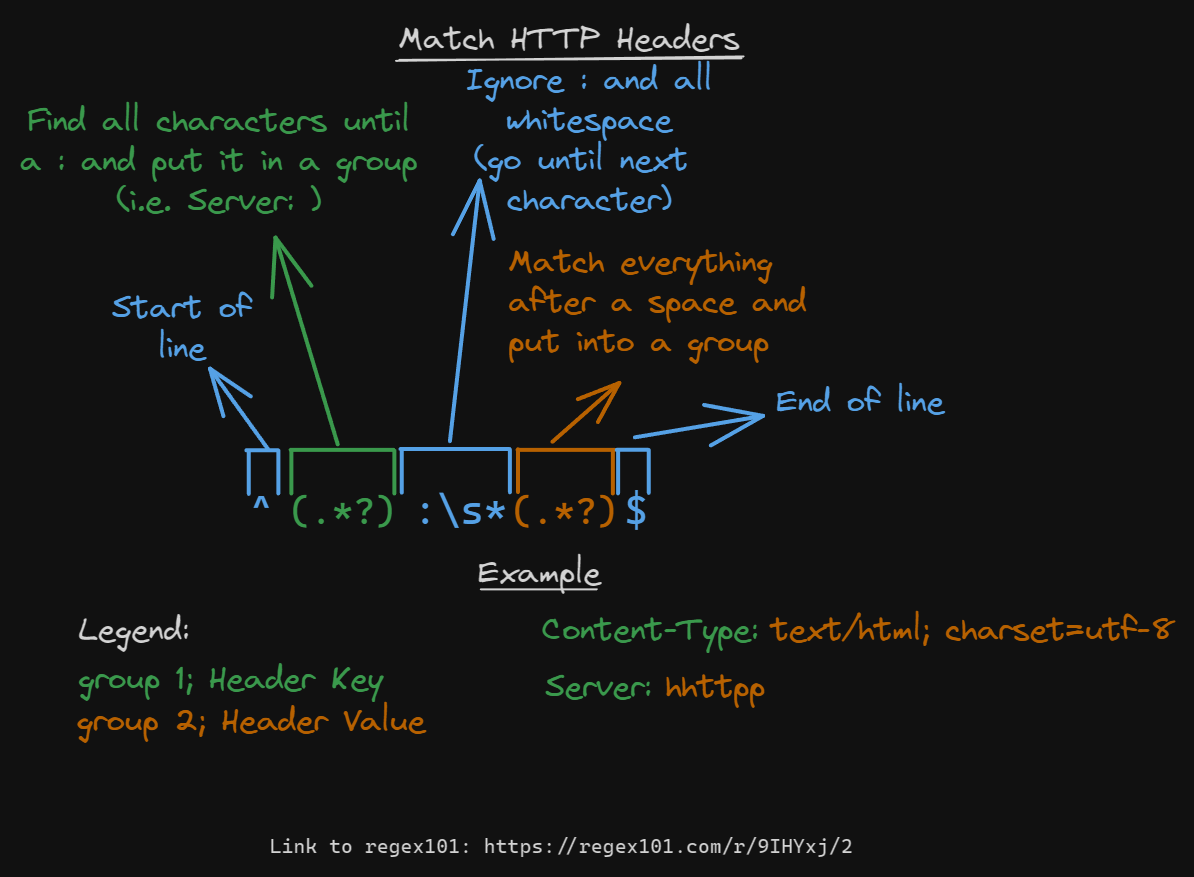

Matching headers

Our first task is to create a pattern to match headers, this will be important for requests and responses, here is the regex for doing this:

So essentially for each match group 1 is the header name, and group 2 is the header value. We can then assign that into a dictionary using group 1 as the key, and group 2 as the value. You can do this with normal strings in python like this:

response = """HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Server: hhttpp

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html><body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body></html>

"""

# Convert response to list of each line and skip the first line

response = response.split("\n")[1::]

headers = dict()

for line in response:

if not line: # Empty line means content starts

break # end loop

line = line.split(":")

headers[line[0]] = line[1]

print(headers) # {'Content-Type': ' text/html; charset=utf-8', 'Server': ' hhttpp'}But keep in mind this iterative approach can have bugs if someone sends a header to the server that is malformed.

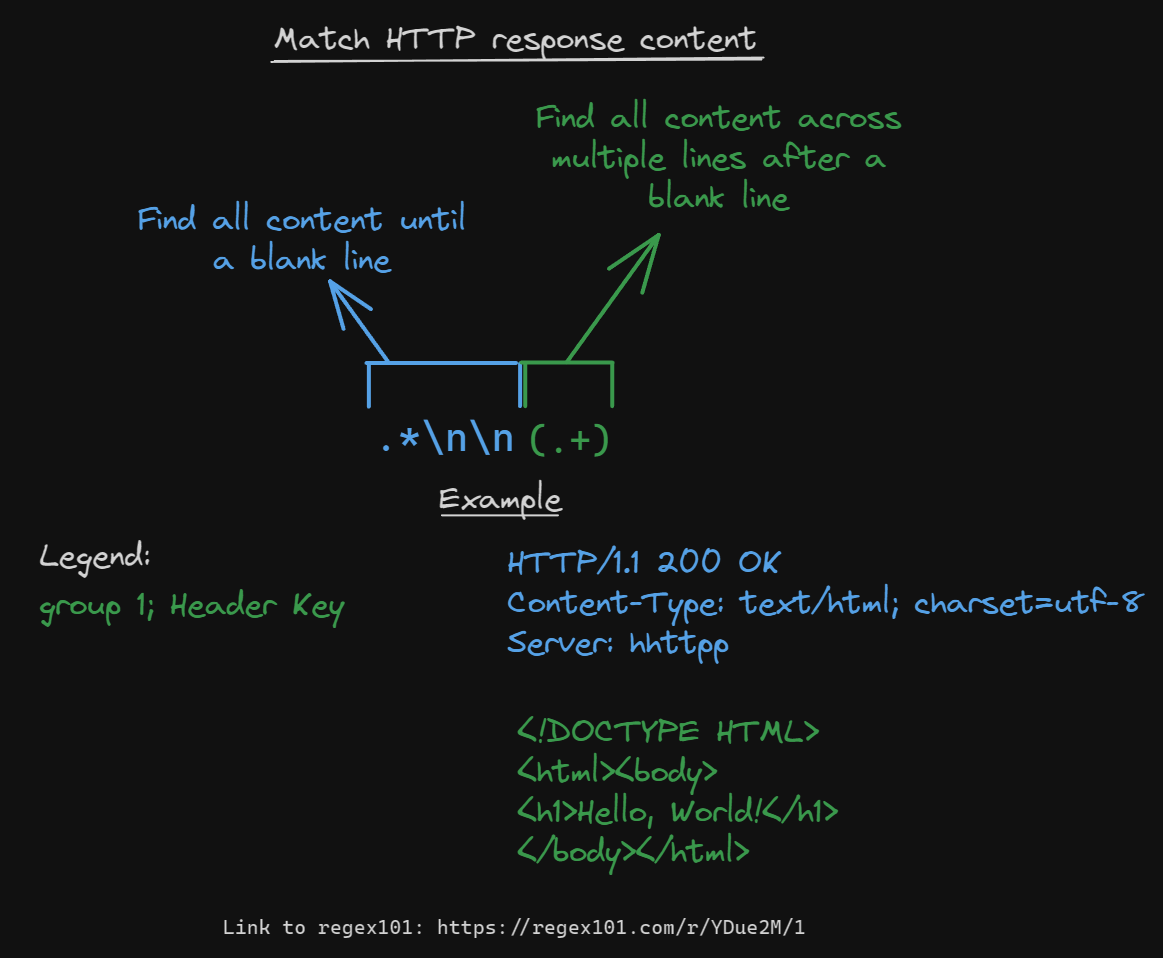

Parse content

For requests and responses we will need the content if it’s there. Luckily this is pretty easy. Content comes after headers and must have at least 1 empty line between the headers and content.

With this one we will need a flag. A flag lets you change the functionality of regex, in our case we must set the /s flag, which will allow us to select multiple lines of content. Here is the regex that works to get this content:

You can do this with normal strings in python like this:

response = """HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Server: hhttpp

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html><body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body></html>

"""

# Convert response to list of each line and skip the first line

response = response.split("\n")[1::]

for index, line in enumerate(response):

if not line: # Empty line means content starts

# Recreate HTML joining each line with a newline at the end

content = "\n".join(response[index+1::])

break # end loop

print(content)Parsing Requests

The main thing we will have to deal with is parsing a request and generating responses. So let’s look at how we will do this.

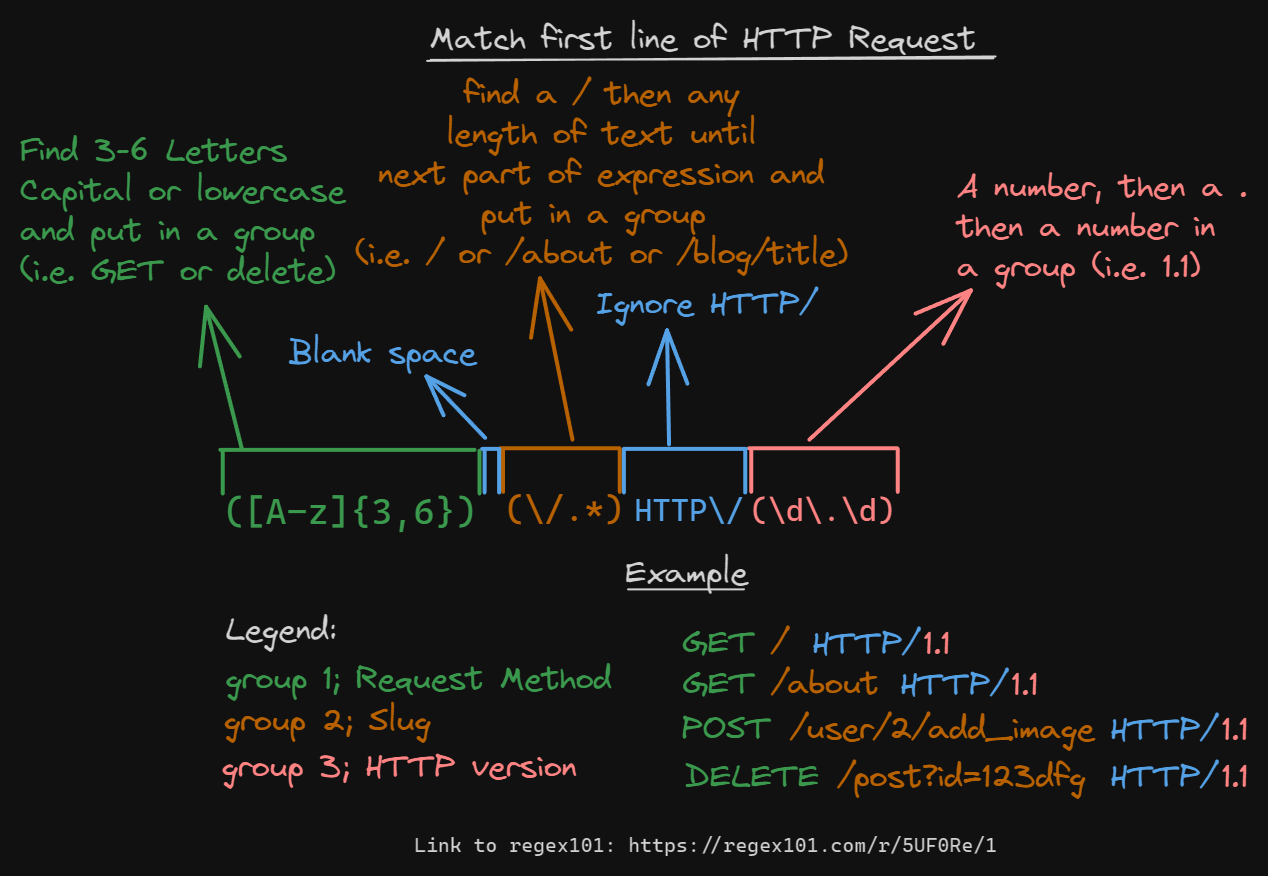

Parsing first line of request

The first line of a request is incredibly important, it contains information about the method used, the slug and the HTTP version. So we need a regex pattern to capture all this information:

You can do this with normal strings in python like this:

request = """GET /low-poly-ice-caps.jpg HTTP/1.1

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Server: hhttpp

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html>

<body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body>

</html>

"""

# Convert response to list of each line

request = request.split("\n")

# Split the first line by spaces, and assign to variables

method, slug, version = request[0].split(" ")

# Convert values to different types (this will throw errors if mistakes are made in the response)

version = float(version.replace("HTTP/",""))

print(f"{method=}, {slug=}, {version=}")Parsing Responses

Now that we can parse headers, content, and requests, let’s look at how we should interpret responses. This won’t really matter for our features, but it will be handy for testing later.

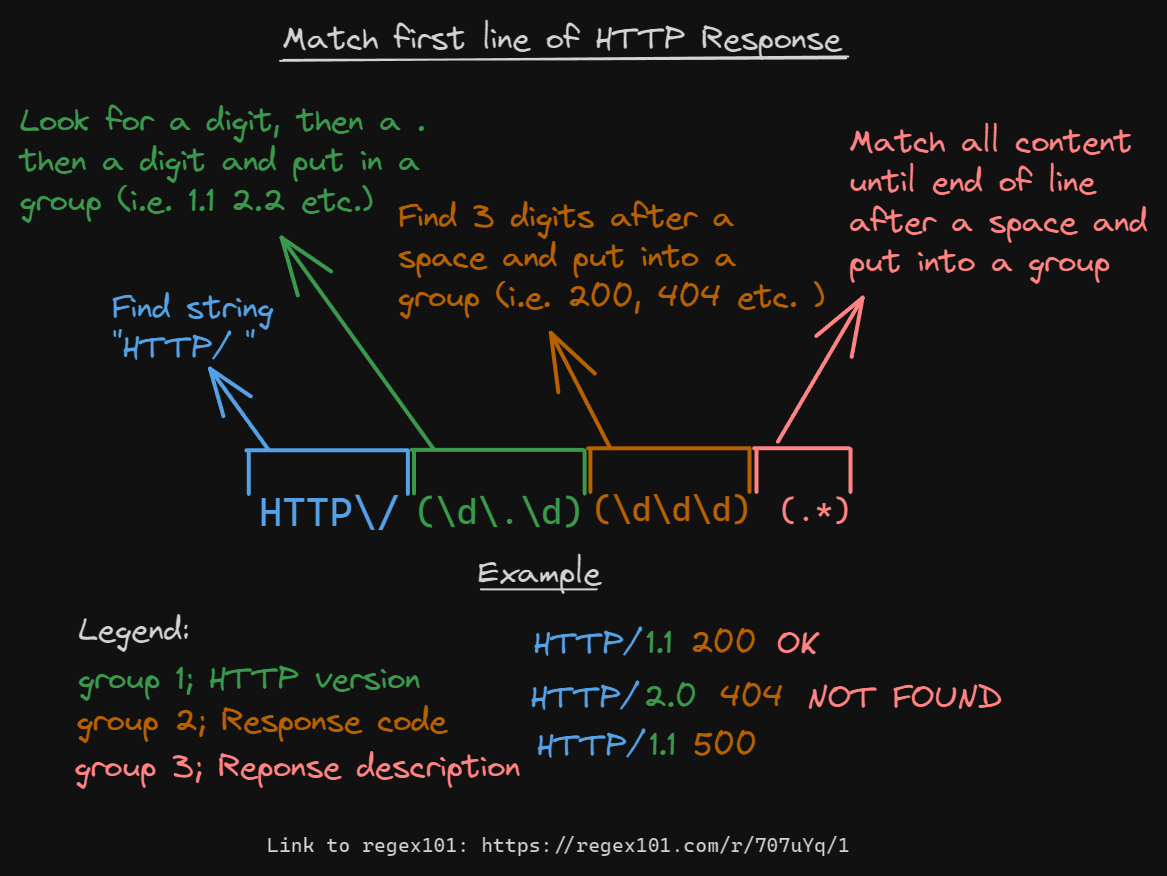

Check first line of response

The first line of the response will have details about a response. As I mentioned this has no purpose in our code, but here is what you would need to do it:

You can do this with normal strings in python like this:

response = """HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html; charset=utf-8

Server: hhttpp

<!DOCTYPE HTML>

<html><body>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

</body></html>

"""

# Convert response to list of each line

response = response.split("\n")

# Split the first line by spaces, and assign to variables

header_version, status_code, response_description = response[0].split(" ")

# Convert values to different types (this will throw errors if mistakes are made in the response)

header_version = float(header_version.split("/")[-1])

status_code = int(status_code)

print(f"{header_version=}, {status_code=}, {response_description=}")