Making Things Small

optimization theory terminology

Crossposted from https://schulichignite.com/blog/making-things-small/

Table of contents

Compression is the art of taking some data and making it smaller. If you want more details about common compression schemes take a look at our definition page for compression. This article is instead going to focus on showing you compression with code examples, and simple custom compression schemes in python!

The repository for the full code examples can be found here

List and dictionary comprehensions

On top of the basic python syntax the code examples use a few concepts you should know.

A list comprehension syntactically shorter way to produce a list of values with a simple calculation. It is intended to replace the design pattern of:

- instantiating an empty list

- Iterate and store values in the list

- return or use list values.

For example:

result = [] # 1. Initialize empty list

# 2. Iterate and store values in the list

for number in range(10): # Square numbers from 0-9 and add them to the result list

result.append(number**2)

print(result) # 3. Return or use list valuesCan be shortened to:

result = [number ** 2 for number in range(10)] # Steps 1-2

print(result) # 3. Return or use list valueswhich produces:

[0, 1, 4, 9, 16, 25, 36, 49, 64, 81]It does exactly the same as the above example, it is just shorter. The basic syntax is [operation for variable in iterable] Were operation is the calculation (or function) being run, variable is the name for the temporary iteration variable made, and iterable is some form of iterable (list, generator, set etc.). We can also do this conditionally, so for example if we wanted to only include even numbers we could do:

evens = [number for number in range(10) if number %2 == 0]

print(evens) # [0, 2, 4, 6, 8]And we can do an if-else statement using:

evens = ["even" if number %2 == 0 else "odd" for number in range(10)]

print(evens) # ['even', 'odd', 'even', 'odd', 'even', 'odd', 'even', 'odd', 'even', 'odd']We can do the same thing with dictionaries. For example:

names = ["Kieran", "Frank", "Amy"]

users = dict()

for name in names:

users[name] = {"new_user":True}

print(users) # {'Kieran': {'new_user': True}, 'Frank': {'new_user': True}, 'Amy': {'new_user': True}}Can be shortened to:

names = ["Kieran", "Frank", "Amy"]

users = {name:{"new_user":True} for name in names}

print(users) # {'Kieran': {'new_user': True}, 'Frank': {'new_user': True}, 'Amy': {'new_user': True}}Lossless vs Lossy

The other concept you should be aware of is that there are two different common ways of doing compression depending on what you need it for. Lossless and lossy. The text algorithm we will cover is lossless, the image one is lossy.

Lossless

Lossless formats are what we’re used to. They take in some data, compress it, and at the end you can decompress it to get back exactly the data you put in. This is handy for things like text (you usually don’t want just some of a text file), or images that need high fidelity. PNG is a format that is a lossless form of compression.

Lossy

Lossy is unlike the systems we’ve seen before. With typical compression we want to get back exactly what we had before we compressed it. With lossy compression we want to be “close”. Imagine you have a large image on a small screen, let’s say a 1920x1080px image on a 480x720px screen. If we were to resize the image and in the process remove 1/8 of the pixels and just stich together a smaller but “close enough” version of the image, most people wouldn’t notice.

Formats like JPG are lossy. They basically create versions of images that are “close enough” to the original source images. This can cause some issues like artifacts, a good quick explainer about this can be found here as a video. Lossy schemes are good for large data like images and videos. Especially when sending the data over a network!

Simple text example

The most common thing we will want to compress is text. We’re going to come up with a super simple algorithm to do this.

There are a few assumptions we’re making for this to work somewhat well:

- Text is in english

- The text does not have any numbers

- The text is general (if it’s a programming language you want to pick different common words)

- The text is at least a few paragraphs (if it’s super short compression is unlikely to be helpful)

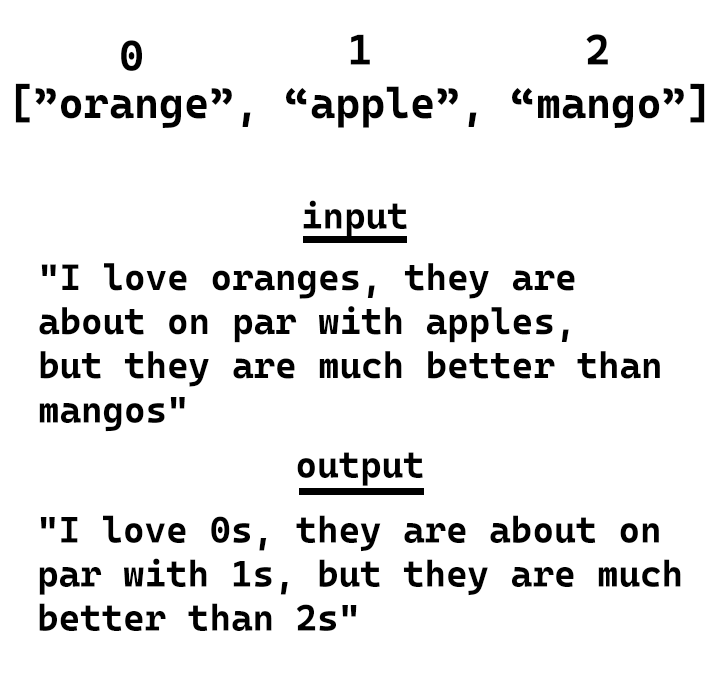

With this the main idea is that we can use the indicies of a list to replace words. So if we have the list words = ["orange", "apple", "mango"] then we can take text like text = "I love oranges, they are about on par with apples, but they are much better than mangos" and replace each occurance of the word with it’s index in the list. So the text would become text = "I love 0s, they are about on par with 1s, but they are much better than 3s", each letter and number is a byte (8 bits), so we saved 13 bytes of space in this example.

The problem is that most people don’t just talk about fruit, so we need to create a list of words that is useful to us. To keep it simple we can just take the 100 most common words in english and hope most text will have them. So the algorithm we’re going to use is this:

- Create a list of the most common english words sorted by length (longest first), include the lowercase and capitalized versions

- Loop over the list of words and replace each occurance of a word in the input text with it’s index in the common words list

So the function would look like this:

def compress_by_common_words(input_text: str) -> str:

"""Takes in some input text and returns the compressed form"""

# 1. Create a list of the most common english words

common_words = [

"compression", "efficient","encoding","data",

"the","at","there","some","my","of","be","use","her","than",

"and","this","an","would","first","a","have","each","make","water",

"to","from","which","like","been","in","or","she","him","call",

"is","one","do","into","who","you","had","how","time","oil",

"that","by","their","has","its","it","word","if","look","now",

"he","but","will","two","find","was","not","up","more","long",

"for","what","other","write","down","on","all","about","go","day",

"are","were","out","see","did","as","we","many","number","get",

"with","when","then","no","come","his","your","them","way","made",

"they","can","these","could","may","I","said","so","people","part",

]

## 1.2 Add capitalized version of the words

common_words += [word.capitalize() for word in common_words]

## 1.3 Sort by length; Longest word first

common_words = sorted(common_words, key=len)[::-1]

# 2. Loop over the list of words

result = input_text

for word in common_words:

## 2.1 Replace each occurance of a word in the input text with

## it's index in the common words list

result = result.replace(word, str(common_words.index(word)))

return resultNow we have our code it’s time to get some text, naturally I figured asking chat GPT to write a few paragraphs on compression would be a good example, so here’s the code for testing our system:

input_text = """"

Compression is a fundamental technique used in various fields to reduce the size of data while preserving its essential information. In computer science and information technology, data compression plays a crucial role in storage, transmission, and processing of large amounts of information. By eliminating redundancy and exploiting patterns in data, compression algorithms can significantly reduce file sizes, resulting in more efficient use of storage space and faster data transfer over networks. From simple algorithms like run-length encoding to sophisticated methods like Huffman coding and Lempel-Ziv-Welch (LZW) algorithm, compression enables us to store and transmit data more effectively.

Compression algorithms employ different strategies to achieve efficient data compression. Lossless compression techniques ensure that the compressed data can be fully reconstructed back to its original form without any loss of information. These techniques are commonly used in applications where preserving the integrity of data is critical, such as archiving files, databases, and text documents. On the other hand, lossy compression methods trade off some degree of data fidelity for higher compression ratios. Such techniques are commonly used in multimedia applications like image, audio, and video compression, where the removal of non-essential information or imperceptible details can lead to significant reduction in file sizes while maintaining acceptable perceptual quality.

The benefits of compression extend beyond just saving storage space and reducing transmission time. Compressed data also reduces the demand for computational resources and improves system performance. When processing large datasets, compressed files can be read and decompressed faster than their uncompressed counterparts, allowing for quicker access and analysis. Moreover, compression enables efficient streaming of multimedia content, making it possible to deliver high-quality videos and audio over bandwidth-constrained networks. By minimizing the amount of data that needs to be transmitted, compression contributes to a smoother and more efficient digital experience, whether it's browsing the web, downloading files, or streaming media.

In summary, compression is a vital technique that enables efficient storage, transmission, and processing of data. It utilizes various algorithms and strategies to reduce file sizes while preserving data integrity or achieving perceptual quality. By minimizing storage requirements, improving data transfer speeds, and enhancing system performance, compression plays a central role in modern computing and communication systems, benefiting users across a wide range of applications.

"""

# Print info

print(f"Original Length of text = {len(input_text)}")

result = compress_by_common_words(input_text)

print(f"Length of compressed text = {len(result)}")Where it gets complicated

With this we get the output:

Original Length of text = 2720

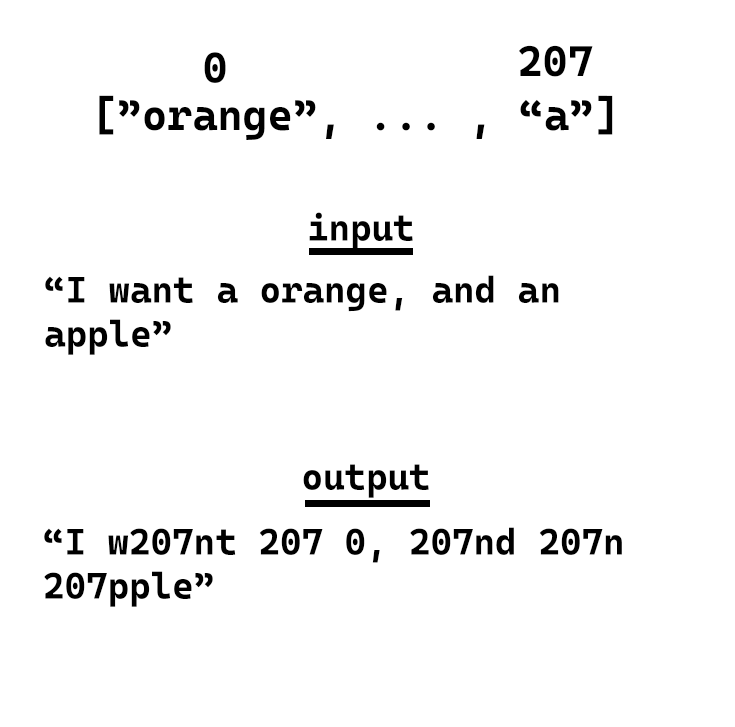

Length of compressed text = 2808AAAAHHH, why is the “compressed” version longer? Well this is part of why compression algorithms are a bit complicated. Our method works, except we made 1 mistake, we ordered our list of common words by length. In theory this should save the most space because the longest words have the shortest indicies (i.e. compression is index 0 which should save 10 bytes per occurance). The problem is short words. For example “a” is index 207, this means we’re actually adding 2 bytes for every occurance of “a”.

Some improvements

When looking at the list of terms remove any term where the index is the same size, or has more digits than the length of text (i.e 12 for “A” would be rejected 103 for “the” would be rejected, but 12 for “the” would work). We can remove all 1 letter words because no matter what we need at least 1 number to represent them which means it will never be compressed. For example is “A” is given index 0 it still doesn’t save any space, so we just don’t include it. This code would be:

def is_word_longer_than_index(word:str, index:int) -> bool:

# Takes in a word and an index indicator and makes sure the length of the word is longer than the digits in the index

if len(word) > len(str(index)):

return True

else:

return False

def compress_by_common_words_improved(input_text: str) -> str:

"""Takes in some input text and returns the compressed form"""

# 1. Create a list of the most common english words

common_words = ... # Same as last example, removed for brevity

## 1.2 Add capitalized version of the words

common_words += [word.capitalize() for word in common_words]

## 1.3 Sort by length; Shortest word first

common_words = sorted(common_words, key=len)

## 1.4 Remove words that are shorter than their index

for index, word in enumerate(common_words):

if not is_word_longer_than_index(word, index):

common_words.pop(index)

# 2. Loop over the list of words

result = input_text

for word in common_words:

## 2.1 Replace each occurance of a word in the input text with

## it's index in the common words list

result = result.replace(word, str(common_words.index(word)))

return resultWith this change we went from 206 items in common_words down to 190, but even though we only removed 16 words the reorganizing gave us the following output:

Original Length of text = 2720

Length of compressed text = 2467That’s ~%10 space savings!

An even Better option

We wasted a lot of space in our common_words list on words that don’t necessarily occur in the text (“day”, “first”, “water”, “oil”, etc.), it would be better if we only included words that occured in the text.

First let’s look at some extra python stuff you will need to know to understand the code. If you skipped it read the comprehension section from the beginning of the article as well.

Counters are a data type included by default in python. They can be used to count the occurences of items in collections (lists, strings etc.). So for example if I had a list of strings representing the results of how people voted for their favourite format of content I could then count the results using:

from collections import Counter

responses = ["audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text", "audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text", "audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text", "audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text", "audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text", "audio", "audio", "video", "video", "text", "audio", "text"]

print(Counter(responses))

Which results in Counter({'audio': 18, 'video': 12, 'text': 12}).

The Algorithm

So our compression algorithm is:

- Create a dictionary of every word in the text with their number of occurences in the text

- Filter the dictionary so that only items with 2 or more occurences are in the resulting list, then sort by length (longest first)

- Remove any term where the index is the same size, or has more digits than the length of text

- Loop over the list of words and replace each occurance of a word in the input text with it’s index in the common words list

import string

from typing import Tuple, List

from collections import Counter

def compress_with_counter(input_text:str) -> Tuple[str, List[str]]:

# Compression using the counter method

# 1. Create dictionary of word occurences

## 1.1 Remove punctuation from input text

counter_text = input_text.translate(str.maketrans('','',string.punctuation,))

## 1.2 Split input text into a list of words so they can be counted

counter_text = counter_text.split(" ")

## 1.3 Count occurances of words in the text

counter = Counter(counter_text)

# 2. Filter to only terms with 2 or more items

terms = {x: count for x, count in counter.items() if count >= 2}

## 2.1 Sort words by length; longest first

words = sorted(list(terms.keys()), key=len)[::-1]

# 3. Remove words that are shorter than their index

for index, word in enumerate(words):

if not is_word_longer_than_index(word, index):

words.remove(word)

# 4. Loop over the list of words

result = input_text

for word in words:

## 4.1 Replace each occurance of a word in the input text with

## it's index in the words list

result = result.replace(word, str(words.index(word)))

return result, wordsWith this approach we get the result:

Original Length of text = 2720

Length of compressed text = 1921That’s ~%30 space savings! While this is great it’s far from as efficient as more complex and robust compression systems (gzip can get up to %90). There is a reason we are returning the words list, and it’s so we can decompress the text later.

So now how do we get back our original text? Well we just go through and replace the indicies with the words right? Well… yes and no. That’s the basic idea, but consider the text 9 12s 254y, the three numbers are (9,12,254) right? Well if we replace indicies one at a time starting from 0 it would be considered (9,1,2,2,5,4) instead. So what we need to do is start from the last index and work our way backwards, so the largest numbers are replaced first:

def decompress(compressed_text: str, terms:str) -> str:

# Decompresses text based on index-replaced compression

result = compressed_text

# Start from last element

index = len(terms)-1

while index >=0:

# Replace each element from end to beginning

result = result.replace(str(index), terms[index])

index -=1

return resultWe will need to pass it the list used to compress the data so we have the correct indicies to decompress it with. So to use it we can do:

result, terms = compress_with_counter(input_text)

print(f"Decompressed text is: {decompress(result, terms)}")Which gives us (text cut off to save space):

Decompressed text is: "

Compression is a fundamental technique used in various fields to reduce the size of data while preserving its essential information. In computer science and information technology, data compression plays a crucial role in storage, transmission, and processing of large amounts of information. By eliminating redundancy and exploiting patterns in data, compression algorithms can significantly reduce file sizes, resulting in more efficient use of storage space and faster data transfer over networks. From simple algorithms like run-length encoding to sophisticated methods like Huffman coding and Lempel-Ziv-Welch (LZW) algorithm, compression enable..."In the real world we would export out the compressed text along with the list of words in some sort of format so we could store it long term and voila.

There’s still a major problem; How can we tell which numbers are part of the compression, and which numbers are part of the text? I’ll leave you to try to solve those problems 😉

Images

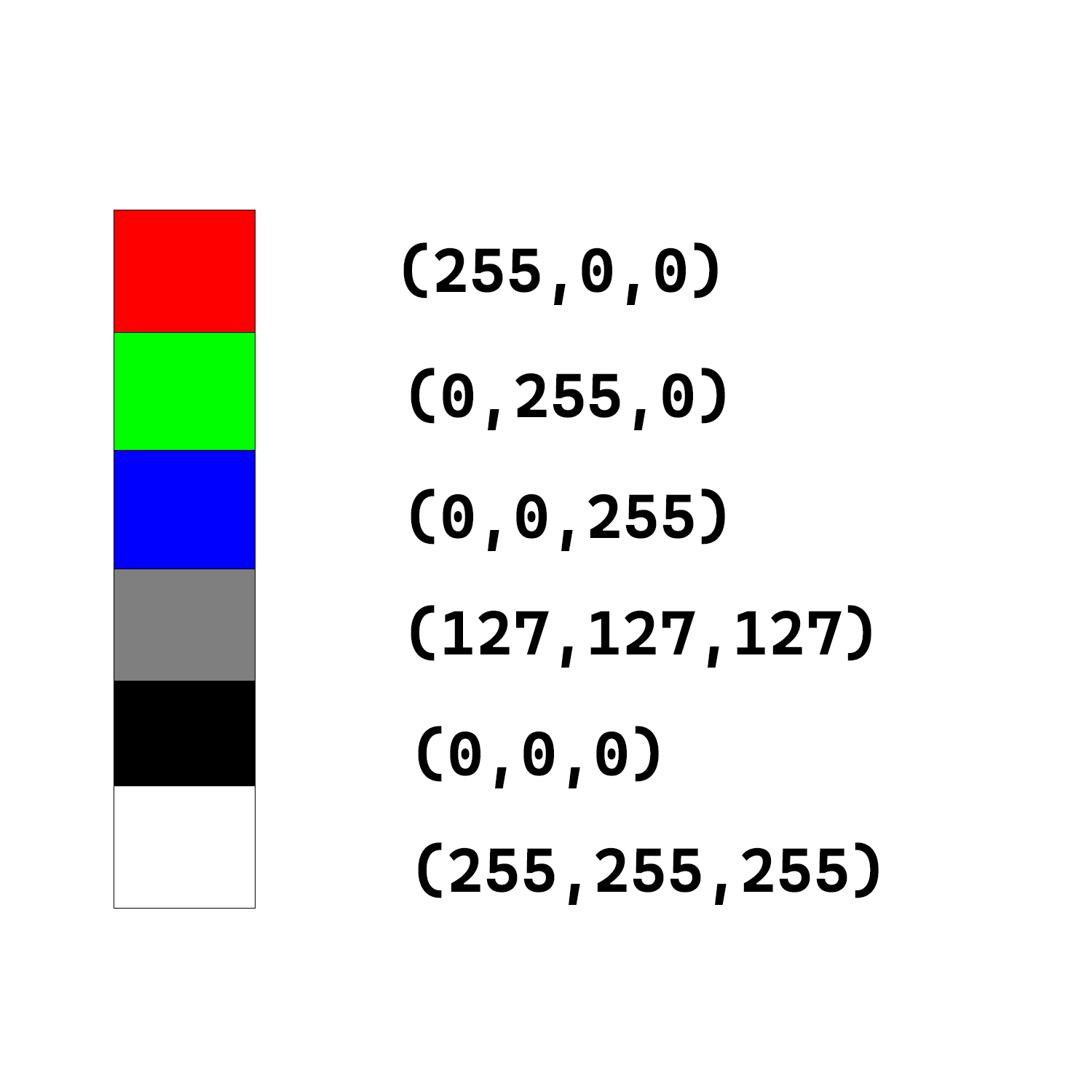

Let’s talk about a quick scheme to compress images. First we need to make up a fake encoding for storing image data. When we are looking at images they are broken up into little squares called pixels. Each pixel in our format will have 3 numbers between 0-255 representing the amount of red, green and blue. So for example if we had (255, 0, 0) that would be 100% red, (0, 255, 0) would be 100% Green and (0, 0, 255) would be 100% blue. Then also something like (127, 127, 127) would be a medium grey (0,0,0) would be pure black, and (255,255,255) would be pure white.

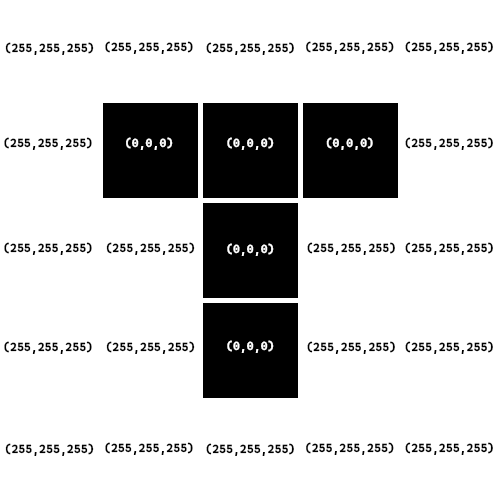

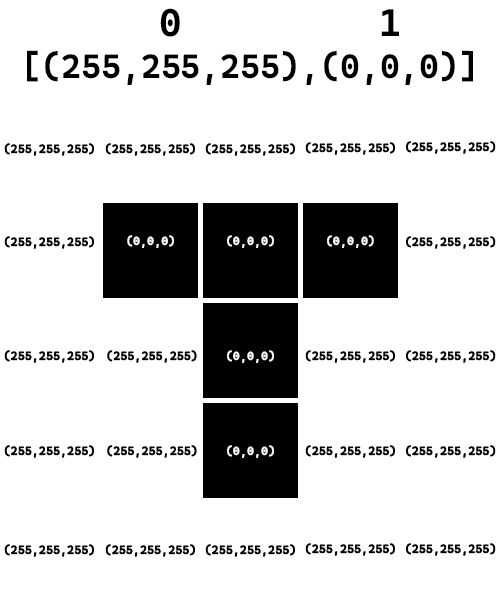

We can then have a list of these tuples of 3 to represent pixels in an image. So for example this 5 pixel by 5 pixel image of the letter T (added white around the black to make the pixel lines clearer):

![]()

We end up with the following representation in code:

image_values = [

[(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255)],

[(255,255,255), (0,0,0),(0,0,0),(0,0,0), (255,255,255)],

[(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(0,0,0),(255,255,255),(255,255,255)],

[(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(0,0,0),(255,255,255),(255,255,255)],

[(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255),(255,255,255)],

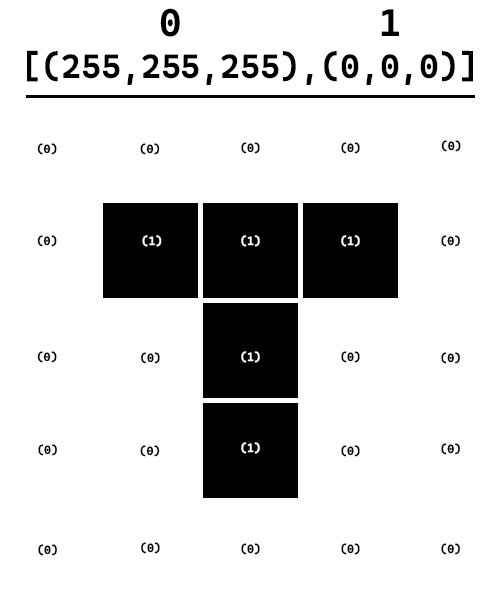

]Here is a visual representation of the mapping:

The algorithm

Now we have our format we can start planning an algorithm

- Round each number up to the next multiple of 5 (except 255, which stays 255). So if we had the tuple

(120, 253, 119)we would get(125, 255, 120)and if we had(255, 0, 1)we would get(255, 5, 5) - Count the occurence of each tupple

- Replace each tupple with the index of where it would appear in the list of occurences, until you reach 11 digits (10 billion item list) or more (since that’s longer than the tuple representation in text)

The first step will make our algorithm lossy, we can be up to 12 bytes inaccurate in terms of colour from the original.

So if we have the example of:

We could compress using:

Then when we decode we just look for tuples of length 1 (like (1) instead of length 3 like (255,255,255))

The code to do all of this is:

from typing import List, Tuple

from collections import Counter

def round_pixels(image_values: List[List[List[int]]]) -> List[List[Tuple[int]]]:

# Takes in a representation of image values, rounds the pixels to nearest number divisible

# by 5 and then returns the new representation with tuples instead of lists

for row in image_values:

for pixel in row:

for index, value in enumerate(pixel):

if value % 5 == 0: # Value is divisible by 5

continue

else:

if len(str(value)) ==3: # 3 digit number

if int(str(value)[-1]) > 5:

pixel[index] = int(f"{str(value)[0]}{int(str(value)[1])+1}0")

else:

pixel[index]= int(f"{str(value)[0]}{str(value)[1]}5")

elif len(str(value)) ==2: # 2 digit number

if int(str(value)[-1]) > 5:

pixel[index] = int(f"{int(str(value)[0])+1}0")

else:

pixel[index]= int(f"{str(value)[0]}5")

elif len(str(value)) ==1: # single digit number

if value > 5:

pixel[index] = 10

else:

pixel[index] = 0

# Convert lists to tuples since lists can't be used with Counter

image_values = [[tuple(pixel) for pixel in row] for row in image_values]

return image_values

def compress_image(image_values: List[List[List[int]]]):

# 1. "Round" pixel values to nearest multiple of 5

image_values = round_pixels(image_values)

# 2. Count tuple occurances

counter = Counter()

for row in image_values:

for pixel in row:

counter[pixel] += 1

# 2.1 Convert to dictionary to make it easier to work with

terms = dict(counter)

## 2.2 Make a list of the terms

common_pixels = list(terms.keys())

## 2.3 Raise an error if the compression would result in larger files

if len(common_pixels) > 10_000_000_000:

raise ValueError("Image has too many unique values to be compressed")

# 3. Replace occurences of tuples with their index in the list of common pixels

result = image_values

for index, row in enumerate(result):

for inner_list_index, pixel in enumerate(row):

result[index][inner_list_index] = tuple([common_pixels.index(pixel) if pixel in common_pixels else pixel])

return result, common_pixelsWe can then test it using:

image_values = [

# Start with third dimension being a list so the values can be rounded (tuples are immutable)

[[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[255,255,255]],

[[255,255,255], [0,0,0],[0,0,0],[0,0,0], [255,255,255]],

[[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[0,0,0],[255,255,255],[255,255,255]],

[[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[0,0,0],[255,255,255],[255,255,255]],

[[255,255,255],[255,255,255],[0,0,0],[255,255,255],[255,255,255]],

]

print(f"Original size of image = {len(str(image_values))}")

result, common_pixels = compress_image(image_values)

print(f"Compressed size of image = {len(str(result))}")Which in our case gives us:

Original Length of text = 399

Length of compressed text = 160Which is not bad, it’s about ~%60 efficient.

and then to decompress would be:

def decompress_image(image_values:List[List[Tuple[int]]], common_pixels:List[Tuple[int]]):

# Takes in a compressed image, and the mapping used to compress it, and decompresses back to original form

result = image_values

for index, row in enumerate(result):

for j_index, pixel in enumerate(row):

if len(pixel) == 1: # Was compressed, convert back to original value

result[index][j_index] = tuple([common_pixels[pixel[0]]])

return resultThis works well, but it cannot run for images above a few hundred pixels by a few hundred pizels because it is very inefficient. You can test this yourself by generating some test data using the following function:

def create_test_data(width:int, height:int) -> List[List[List[int]]]:

# Generates test data to be used with compress_image()

result = []

for row in range(width):

current_row = []

for column in range(height):

current_row.append([random.randint(0,255), random.randint(0,255), random.randint(0,255)])

result.append(current_row)

return resultTesting with:

image_values = create_test_data(200,200)

print(f"Original Length of text = {len(str(image_values))}")

result, common_pixels = compress_image(image_values)

print(f"Length of compressed text = {len(str(result))}")

print(f"Compression ratio is ~%{((len(str(result))/len(str(image_values))))*100}")Which gives us:

Original Length of text = 628658

Length of compressed text = 386393

Compression ratio is ~%60.9185562166747It took a min or two on my machine, but at 500,500 it still wasn’t done after 5 mins. The scaling is very poor because it has to check every value of every pixel, so for 200x200 that’s 40,000 checks, and for 500x500 that’s 250,000 checks and for each pixel we need to round the values 😵💫. Try to figure out a more efficient way of doing this if you can!

File types

There are generally 2 types of files:

- Text files

- Binary files

Text files are just plain text that have some sort of encoding. They are meant to be readable and are used for things like source code, plain text files, markup files etc.

Binary files are files that either:

- Are meant to be run with a specific program (i.e. PDF’s need a PDF reader, images need a photo viewer etc.)

- Are meant to be executed (i.e. an application)

For images you will mostly be working with binary files, these are a bit different than text files. With text files it makes sense for us to simply read each word or letter, with binary files the organization of data changes by file type. For one file like a binary format spreadsheet maybe you want all the data until a ; or , in the file, whereas for images you may want tuples of 3 numbers (255,255,255) which correspond to RGB values.

Each binary file differs in how you want to read it, so be careful when working with them. For most image-related activities check out pillow for python!

Video

This article is already long enough so we are going to skip video because it’s quite a bit more complicated. See the section below for common real-world examples, and take a look at our section about sampling in the compression defition.

Real world compression systems

Most real world compression systems are based on the encoding they use. But here are a few examples you can look at:

Text

Algorithms that make up common compression systems

- Huffman Coding (this solves the problem of numbers in our algorithm)

- LZ77/LZ1

- Deflate

Common compression systems (Use deflate, huffman coding, and LZ77/LZ1)

- Gzip; A generic compression system used in most browsers and applications

- Brotli; A webpage optimized compression system

Image

- JPG; Very common lossy image compression

- This video

- These two videos from computephile

- This set of articles

- PNG; Common lossless image format that also supports transparency

- Base64; A text-based way of storing image data

A good broad topic video can be found here

Video

- MPEG; Set of formats used for videos (mpeg-4 is also known at

.mp4files) - h.264; THe encoding used for most videos on the web today

Most commonly videos are MPEG-4 (.mp4) using a h.264 codec to encode the data. A good broad topic video can be found here