Imagine the room you are currently in is being engulfed in flames. At this point you’re probably thinking “AAAAAGGGGH”, but why? Well the pain of being burned is probably a good explanation, not to mention the smoke inhalation making you feel like you’re about to black out. At this point if you’re lucky a strapping firefighter comes in to break down your door and whisk you to safety. After agreeing to buy one of their calendars (obviously) you probably have a better understanding of why people call firefighters brave. I would argue one of the main reasons for this is them showing courage in the face of danger. That same pain of being burned, and the threat of death was looming for them, yet they overcame it, and willingly entered to help you out of the building. In fact we could change a single variable, and likely no one would call them brave anymore. What if we made them fire-proof?

What if the firefighter in the above example had no chance of harm? They could walk through whatever flames and be fine. They could breath in all of the fumes and still be a happy camper. For them walking into the building is basically like walking into any other house. Would this firefighter still be a hero for what they do? or would their work constitute being mundane? You might even say being in a house that is structurally unstable is dangerous, so what if we removed all danger, and instead the firefighter operates a robot that acts for them. Is there still the same sense of bravery? The situation hasn’t changed at all, but the person has, so what attributes does an individual need to effect this courage?

Let’s not get too fantastical

If everything seems under control, you’re not going fast enough.

- Mario Andretti 1

Mario Andretti is an ex racer (formula one, NASCAR etc.). Undoubtably an incredibly difficult job to get up, and often put your life on the line for fame, money, and glory. That being said if I were to get in a car and drive at his speeds it would not be admirable, instead people would likely consider me suicidal. The reason for this is the obvious difference in experience. Yes Mario was taking on risk while he was driving, however the risk is calculated. The risk is within a range that allows for the thrill of competition, while not just being a simple dice roll every day on the track. If I were to get in the car without training however there is no reward, there’s just risk. I lack the personal skill to even be considered for any form of greatness at racing, and so trying to attempt it is just risk for risks sake.

I think this is important to keep in mind because it illustrates 2 incredibly important points about courage and risk:

- Each person’s difficult is different

- Each person’s difficult changes over time

You are a special snowflake

Comparing me to Mario when he was racing we can see that difficulty scales to each person. Likewise unless there’s a long history of a skiing background I am unaware of, Mario would be in incredible danger on some of the slopes I ski. In these cases the act itself is not where the courage lies. The line between courage and stupidity has been crossed if I were to enter into a formula one car, and instead of courage I’m just being irresponsible and endangering myself and others. The courage instead lies in having the reasonable potential to achieve, and achieving in spite* of the danger. This differentiation can be called the subjectivity of consequences.

For me the willingness to go skiing and ski what I ski could be called brave (though I’m less certain of it these days), but only in conditions that are still providing shelter from being just random chance. If I broke my leg and then went skiing, we would again likely cross over into the irresponsible side of things. I would argue that we should engage in acts of bravery and courage where possible, because the difficulty it proposes is important to continued growth. As such whatever situation challenges you and provides a sufficient challenge relative to the reward balanced against the risk. The formula for this would be:

(Reward * Challenge) - (Risk * Challenge)

Snowflakes melt

While Mario was an incredible driver it is probably not a good idea for him to drive those speeds now. The difficulty and risk of driving has changed over time to a point where it would no longer be worth it. The danger potential has tipped the scales and become too dangerous relative to the potential to achieve and do something admirable. This can often happen, and it will opt us out of being able to do the things we want to. However this knife cuts both ways.

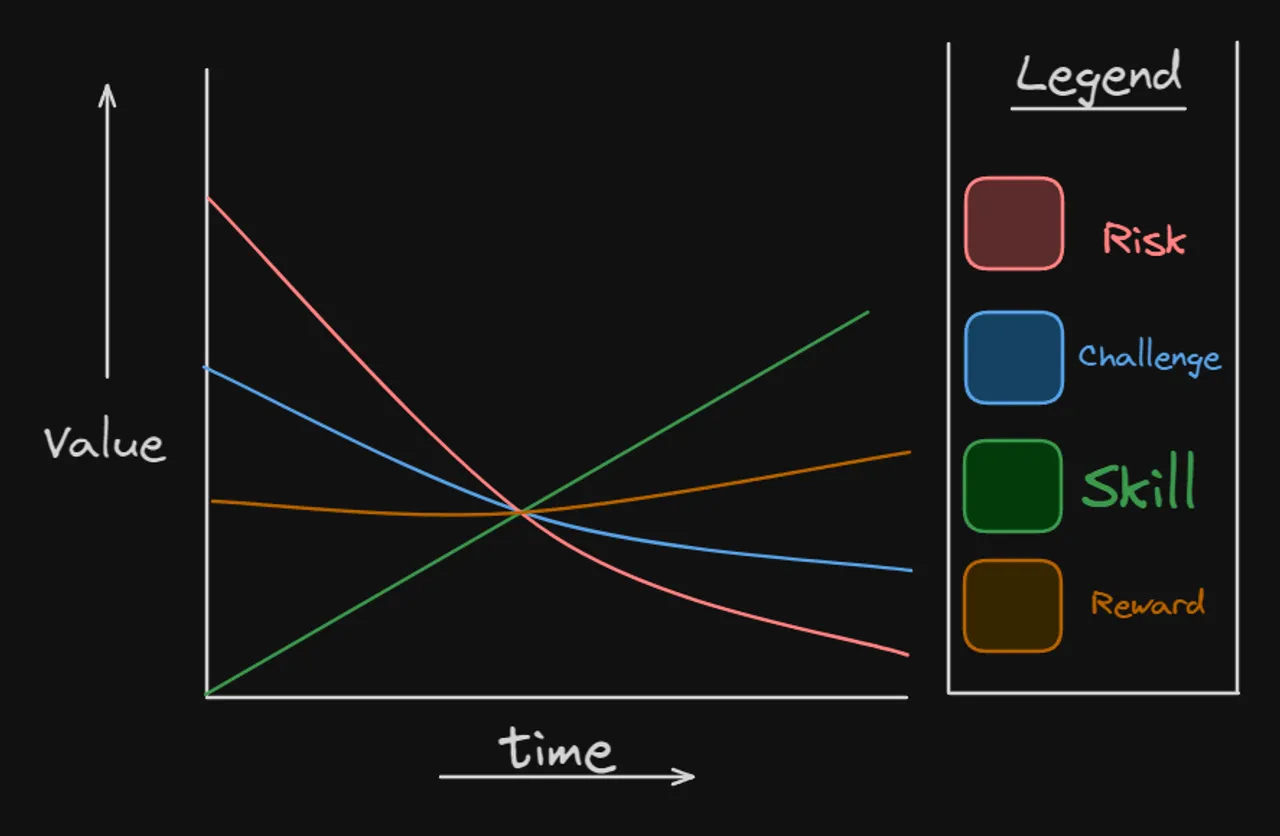

Often times people can become complacent, and in that complacency we find people who are larping as courageous, while being mediocre. Over time the amount something challenges someone changes. In fact all three variables of our equation, risk, reward and challenge will change over time. Within the same person it is possible eventually for the thing that made them brave to be what keeps them cowardly and comfortable. At one point I was afraid of skiing black diamonds. They were incredibly dangerous, and I was more likely to injure myself than complete a single run. Likewise single black diamonds I didn’t consider very impressive. The values for the function might look something like this:

Reward = 50

Challenge = 150

Risk = 200

(Reward * Challenge) - (Risk * Challenge)

(50 *150) - (200*150) = (7,500) - (30,000) = -22,500Now as I got better the challenge goes down, but the risk goes down much more and as time goes on the reward slightly goes up because more people expect you to have more accolades as your skill builds:

So it may now be:

Reward = 140

Challenge = 130

Risk = 100

(Reward * Challenge) - (Risk * Challenge)

(140 * 130) - (100 * 130) = (18,200) - (13,000) = 5,200At this point since the number is positive and decently large, it’s probably worth doing. But with current date and time however, doing a black diamond run is not courageous for me. The challenge has been lowered sufficiently enough that it sets the reward way too low:

Reward = 40

Challenge = 30

Risk = 20

(Reward * Challenge) - (Risk * Challenge)

(40 * 30) - (20 * 30) = (1,200) - (600) = 600So it still might be worth doing in an abstract sense (fun), but it has no value or bearing on courage or improving myself.

As a short justification of this measurement let’s talk about the constituents. Reward is mostly there because it’s important to consider what you can gain so you don’t avoid dangerous, but high risk, high reward situations. Challenge is largely a theoretical stand-in. Challenge represents the possible difficulty as assessed by the person. This possible difficulty is in the positive case, meaning it’s the difficulty if nothing weird happens (weather, freak accidents etc.). Risk on the other hand is there to keep challenge in line. Risk is where you do a pessimistic accounting of the challenges you could propose that cannot be guaranteed to be accounted for. The challenge of a mountain might be it’s steepness, and the shape of the slope, the risk of a mountain might be the lighting on the specific day, obstacles I don’t know that are hiding in the snow etc. The reason risk goes down over time is because things like obstacles hiding in snow can be better accounted for over time (better balance, able to ski on one ski etc.), not necessarily a matter of doing risk mitigation (removing the obstacles etc).

Let’s not get too post modern

Ready must thou be to burn thyself in thine own flame; how couldst thou become new if thou have not first become ashes!

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra 2

One problem with this view of “subjective consequences” we do run into a potential issue. One more common occurrence these days is that the type of consequences that people consider “brave” to face are very nonchalant. Anecdotally I have heard people calling others brave for posting on social media anonymously a mainstream argument. In their mind the potential of even a single anonymous disagreement being voiced is a high enough bar to be considered a courageous consequence to overcome with bravery. I would completely disagree, however what measure can I actually use to ground this disagreement? What is a “sufficient consequence” to be courageous if one overcame it?

There is no satisfactory answer in an objective sense. Likewise my own personal feelings illustrate a danger present in the normativity of courage. To reiterate again what was said earlier, everyone’s version of difficult is different, and therefore everyone’s form of being courageous is different. My argument is that an objective measure such as what I was suggesting doesn’t help anything. Instead if we want to argue for a set of “essential difficulties” people should be able to overcome I should just set that standard as an expectation. For the people I described earlier they would have to be more courageous than others to achieve these ends, but difficulty is not an excuse for mediocrity. We can identify someone might struggle, and we should try to uplift them, however the fact that something takes courage to do does not “let them off the hook”.

For me I am type 1 diabetic. Every meal I eat poses a potential health issue. DKA (Diabetic Ketoacidosis) if I eat too much sugar, and Hypoglycemia if not enough. Let alone long term complications like diabetic neuropathy. That however isn’t an excuse for anything. It is a challenge that is presented, and the diagnosis presents a set of procedures I have to follow. When I used to have to do needles it was a scary prospect to eat, and sometimes I would skip meals because of it (these days it’s 1 needle every 2 days, which is more manageable).

The dangers of life are infinite, and among them is safety

- Goethe 3

The skipping meals does not turn from being poor (in terms of health outcomes) to good because it’s more understandable, it’s simply more understandable. Anyone can empathize with why meals would inherently cause more anxiety, however that isn’t carte-blanche to use it as an excuse not to do something. You may need to have bravery or courage to do something, even something as simple as eating, or for others maybe the anxiety of talking to another person about something difficult. It is worthwhile to normatively load courage and bravery, but “not being brave” also cannot be a sufficient excuse not to do bare necessities in life.

Conclusion

It’s good to push yourself. It’s good to be brave and do things that are courageous. This needs to be tempered with avoiding endangering yourself pointlessly for ego, or some other small reward. It is a careful (and subjective) balance that needs to be met, but it’s one worth doing the calculations on every so often.

Footnotes

-

Quote by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: “The dangers of life are infinite, and among the…” | Goodreads No proper citation provided, though claimed to be a part of Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, however I’m not sure which translation it is from ↩