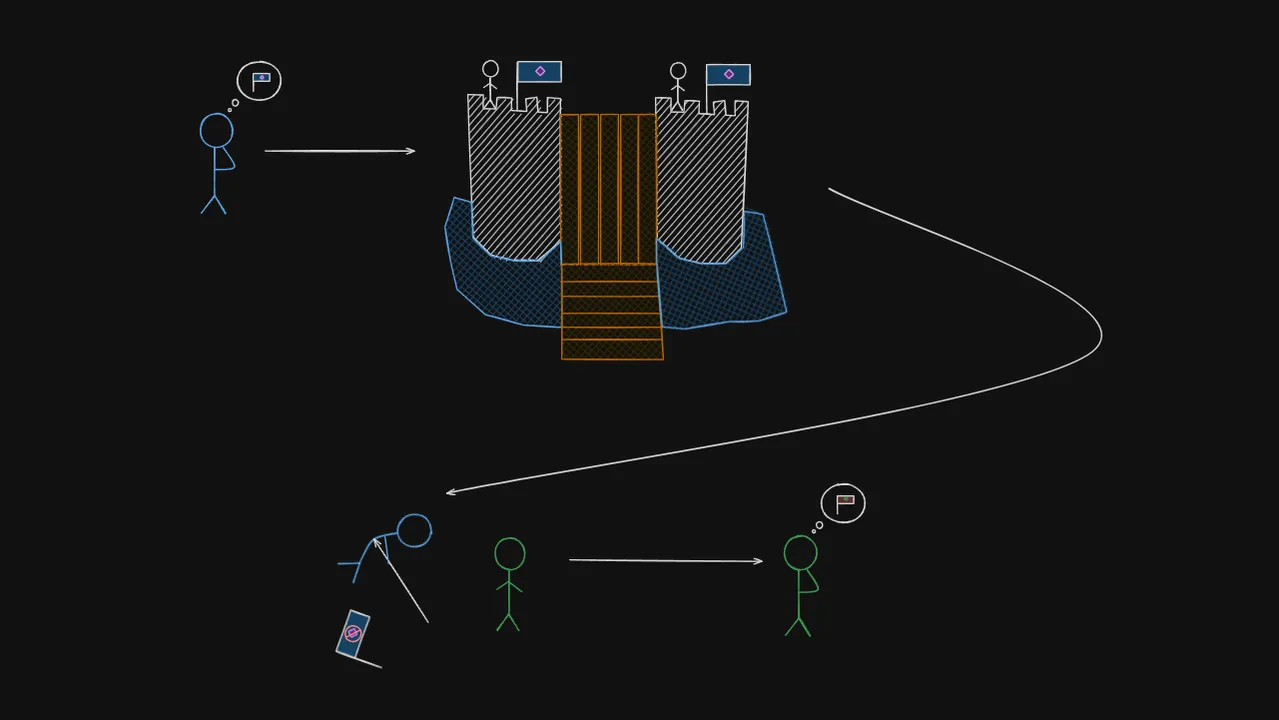

Imagine you’re on a new planet, it’s exactly like earth except where you are does not have a country, and everyone has no memories of what came before. You are in charge of creating a new country in whatever image you want, whatever laws and policies you want. For the sake of this argument assume we have the backing of everyone on the planet to see as we do fit. Now if we did the same experiment with someone else, would you end up with the same structure? Probably not. We often take for granted a lot of the axioms and philosophical underpinnings that allow our society to function how it has. One of the main ones is, what are the philosophical underpinnings of how a state acts, and legislates?

When we ask ourselves for example why murder is wrong something like “people deserve a right to safety” often comes up, but this answer begs the question. Why do we have the rights we do, and how did we even come up with them?

The first pillar

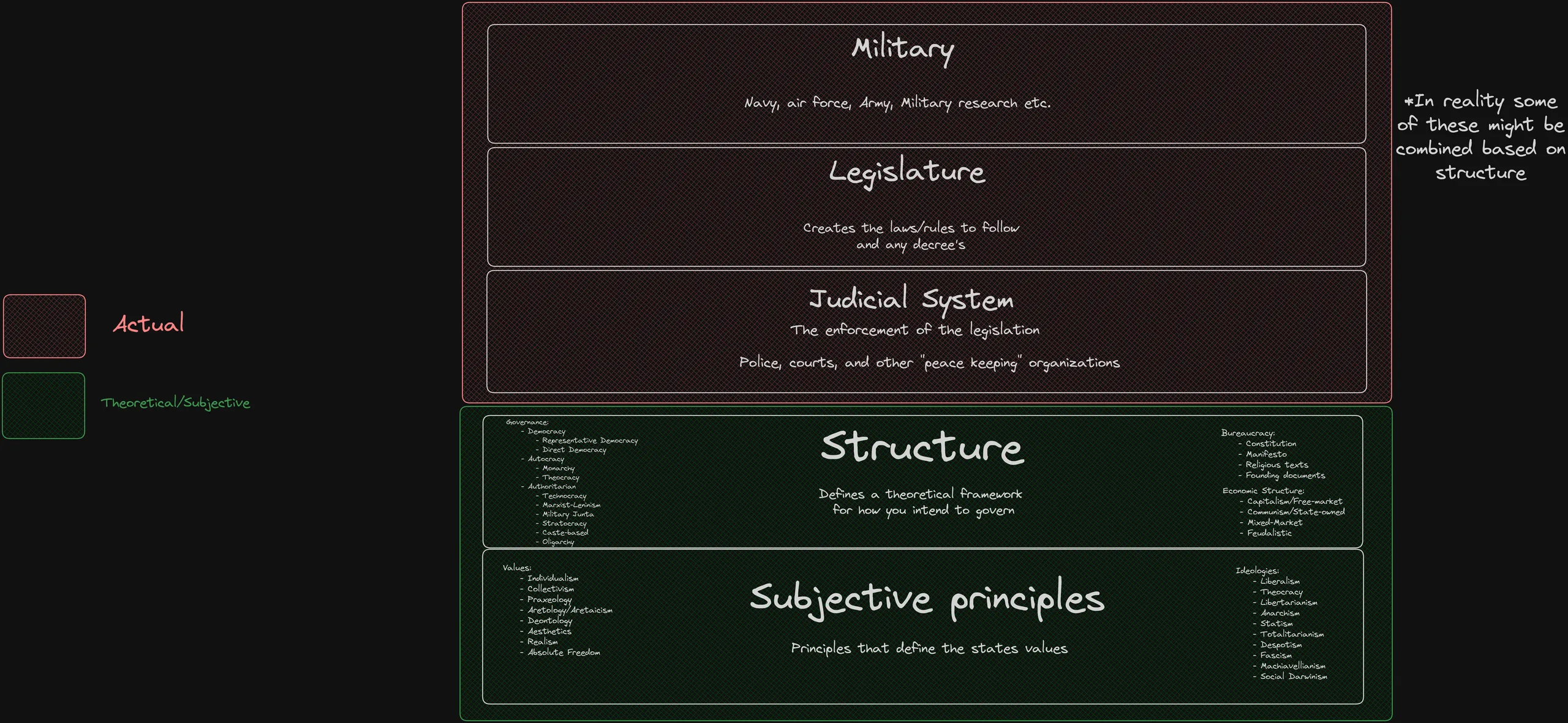

When building the system that defines a state, it all starts with subjectivity. Each state will have a philosophy that stands on top of subjective decisions both implicit and explicit. In the secularized west this typically follows some formulation of people having individual worth, and some formulation of freedoms that follow from this. If instead we were in a religious monarchy the state foundation would be one of the divine right of the king to act as he saw fit, and/or religious law. If we were in a statist society it would be that the needs of many outweigh the needs of the individual. No matter your position you start from, it is always subjective.

One of the best lines of questioning to support this argument is “why do we care about the scientific method”? The answer at first seems obvious, but gets harder when you need to try to specify it objectively. A good example I’ve heard (and what I believe) is that science as an institution values predictability, predictability allows for stability through expectations, those expectations allow us to plan ahead and have control over life. The last part of that statement was a value statement. Specifically that control through the ability to accurately predict (and therefore expect) events is a “good” thing.

- it’s good because that stability allows for long term planning

- it’s good because you can materially outpace societies with scientific advancement

- it’s good because it provides self-evident avenues of inquiry for people to be interested in (people can falsify and validate it themselves)

As such the scientific method being implemented as a way to rationalize things is “good” because it provides everything mentioned above. However we could decide that is a bad thing. We might instead say that the beauty of life is in the ignorance of not knowing. That the decision based on intuition, and the trust placed in oneself is a higher virtue than stability, predictability, and control. Once we have a set of these sorts of principles we can start to construct a state.

It’s important to note that this description of philosophy into statecraft is not historically accurate. Historically states are built on the corpses of what came before them, and as such there is a more natural ebb and flow of these underlying principles throughout time, which then effect the state from there. But like I said in the beginning, we’re on a new planet and we’ve got nothing to go on, so we’re doing it live. We should try to have a document to record this somewhere. A constitution, or some other founding document is probably a good call.

Structure

Once we have the principles laid out we need to figure out the structure. Our principles will largely determine this. For starters how do we distribute the power of our new state? If we decide that we believe individuals should have a say in governance we can go the democratic route, if we believe only “the best” should decide then we go autocracy. Within those decisions we need to choose representative democracy, direct democracy, monarchy, technocracy etc.

Each have their benefits and problems, but in general whichever is chosen should probably align with some sort of justification from our founding principles. If you’re part of a religious group that believes that one man is an emissary of the divine on earth and they are a better person than everyone else democracy doesn’t really make sense. Why would you not have the better person making choices? Likewise if you believe individuals have worth and should have a hand in their own destiny, but decide one person should make all the decisions with no accountability it doesn’t make much sense. At some point either the structure changes, or the principles.

If the state is large enough you may need to create enclaves of state power such as provincial/state government organizations, municipal organizations and topic-oriented agencies (environmental protection, consumer rights etc.).

Now we know how we distribute power who can take that from the people. Time to plan out how justice, legislation and other governing bodies effect each other.

Self-perpetuation

It’s important to note at this point that much like the state justice is self-perpetuating. A state perpetuates itself only in it’s ability to maintain it’s own stability (however that looks), power and influence. Justice is simply the ratification of the morality we determined in the founding documents. A just sentence is one that acts in accordance with the principles of the founding documents, and the procedures and beaurocracy of the judicial system. This is what makes justice an inextricable part of the state it operates in. There is no justice without context and that context is the state and it’s underlying principles.

Change

Priorities will shift inside a state, and so how do we decide when to diverge from our founding principles. This is also up to the structure chosen earlier. Potentially democratic reforms, or even potentially you can’t change. Depending on what the citizenry wants to do you may need to diverge so far from founding principles that you can’t do it without dissolving the state. At that point things will start getting uncomfortable. We have seen this in many autocratic and religious states over time where their dogmas make them unable to adapt, and eventually the citizenry revolts. At which point a new state is formed from the ashes and often follows a similar set of founding principles, but with changes. This last aspect is what’s driven most of the cultural and societal advancement (depending on your view) of the last few millennia.

Conclusion

So there you go, it’s super simple. Just correctly select a set of foundational principles that make people happy, develop governance using it, and hope you can hold onto that power long enough to flourish. In reality every individual step mentioned would at best take years to properly flesh out, and many countries are still in this process now. Statecraft from this perspective is simple, but not easy. The smallest individual choices at any of these levels can cause massive changes in the resulting state.