Humans are social creatures. We form complex relationships to one another. We also spend a tremendous amount of time trying to understand each other. Ostensibly working towards forming a closeness to one another. But how close can we actually be to one another?

Hell is other people

Hell is other people

- Jean-Paul Sartre, No Exit

Sartre was an incredibly pessimistic person. The quote in No Exit is used by angsty nihilistic teens and more jovial philosophers alike, because it’s more than it first appears. When Sartre first wrote it he largely crafted it in the context of what it means to be seen. Hell is other people, because engaging with others forces you to understand yourself in a way similar to how you understand them. People understand others as an object; A collection of relations you have to them. The experiences, gossip, preconceptions and judgements you have of other people is how you understand them. Sartre noticed that if this is the case then you yourself are being recognized by them through the same mechanisms.

Self-consciousness

Because of this “hell is other people” because others force you to see yourself as an object, as an “other” in peoples perceptions. Even worse we have to use a low resolution view of their perceptions since we’re not in their mind. So, not only is their perception an incomplete bundle of ideas, but our perception of their perception is just a statistical guess. Whatever they believe about you, and however they relate to you is fully in their control, ineffable, and isolated.

The quote is broadly seen as pessimistic. The notion that others inspire self-conscious thoughts in your head is typically considered a bad thing. Additionally people often assume others think much worse of them than they think of others 1 2. Unfortunately it gets worse before it gets better.

Distance from yourself

There is an argument to be made that even your own self-perception is incorrect. You observe yourself, but in order to do that there has to be a “you” doing the observing. The problem then is not just that others cannot perceive you, but that you cannot perceive all of you. We often understand this as your “unconscious” mind. The parts of you that you often don’t understand, and are revealed to you in the shadows of your actions rather than as directly observable thought processes. Not only is there a limiting case to the closeness you can experience with others, but even the closeness to yourself is not immune.

Asymptotes

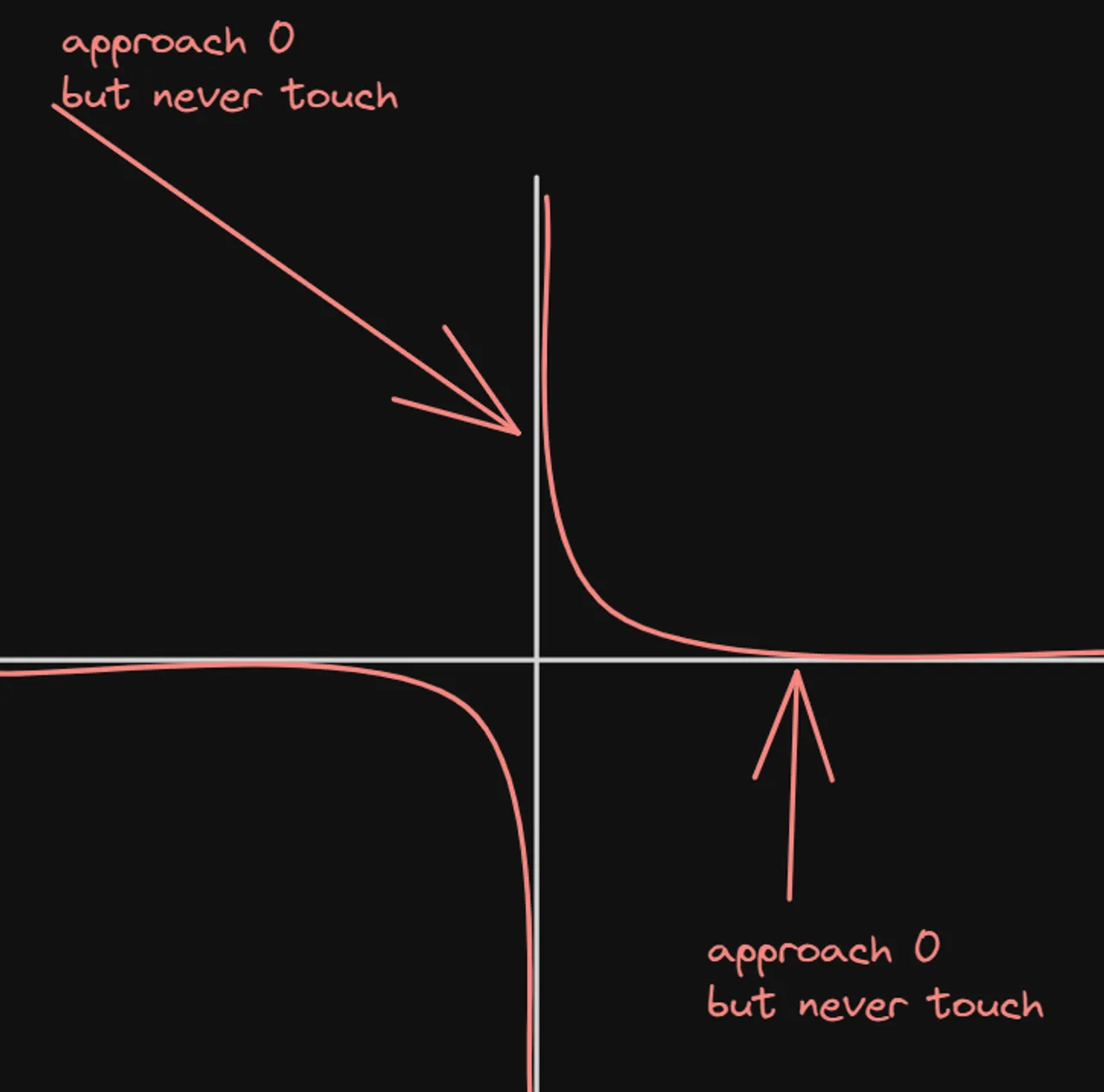

This pattern of simultaneous closeness, and distance comes up in other places and fields. An asymptote is a mathematical term that has a proper mathematical definition (words and everything!), however it’s most easily explained with an example. In a graph an asymptote approaching 0 is a graph where a line will approach 0, but never touch it. It will get infinitely closer, but there’s still an infinity between it and ever actually touching 0.

The important point with this visual is that no matter how close it seems to be to 0, there’s always an infinite, and insurmountable distance.

Being less miserable

There is however a more romanticized interpretation of this quote, specifically in relation to why this is considered a bad thing. The only reason this could possibly be bad is the recognition that what you are, and who you are is only ever accessible to you. You, as you perceive yourself is trapped in your own head. No matter how close you get to someone, you can never “truly” understand each other. Much like an asymptote the fight for closeness to another person is infinitely large, no matter how close you seem to get. So, that’s case closed, right?

Possibly, however I think there’s a few underlying assumptions that are making this situation seem more dire than it is. But first we need to explore each case of asymptotic closeness more closely, and introduce a third interesting case.

Closeness to yourself

The first relationship is at the individual level. How close can you be to yourself? It seems to me that the answer lies in a combination of 3 sets of patterns:

- The conscious thoughts you have

- The actions you take based on those thoughts

- The patterns identified in how those conscious thoughts come to be

Starting from the last point it’s very important to understand your thought process. Understanding why you have certain reflexive responses, and even more active responses is important. People often say that in journalism it’s most important to be impartial, but in your mind you never will be. There will always be underlying mechanisms, biases, complexes etc. in your brain that inform your thought process, and working to understand those is a great way to get to know yourself.

Lastly it’s important to understand which actions you actually take. Arguably the actions you take indicate “the most important” parts of yourself. Soren Kierkegaard spoke about a delineation he made called the spiritual vs actual self. This is probably easier to understand as the possible vs real self, wherein the possible are the things you have the capacity to be, and the real is what you currently are. Anyone could think of themselves as an athlete, but only those who act like athletes are broadly considered to be them. The identification can be possible or real, but actions taken in service of those beliefs are what you really are.

Transience

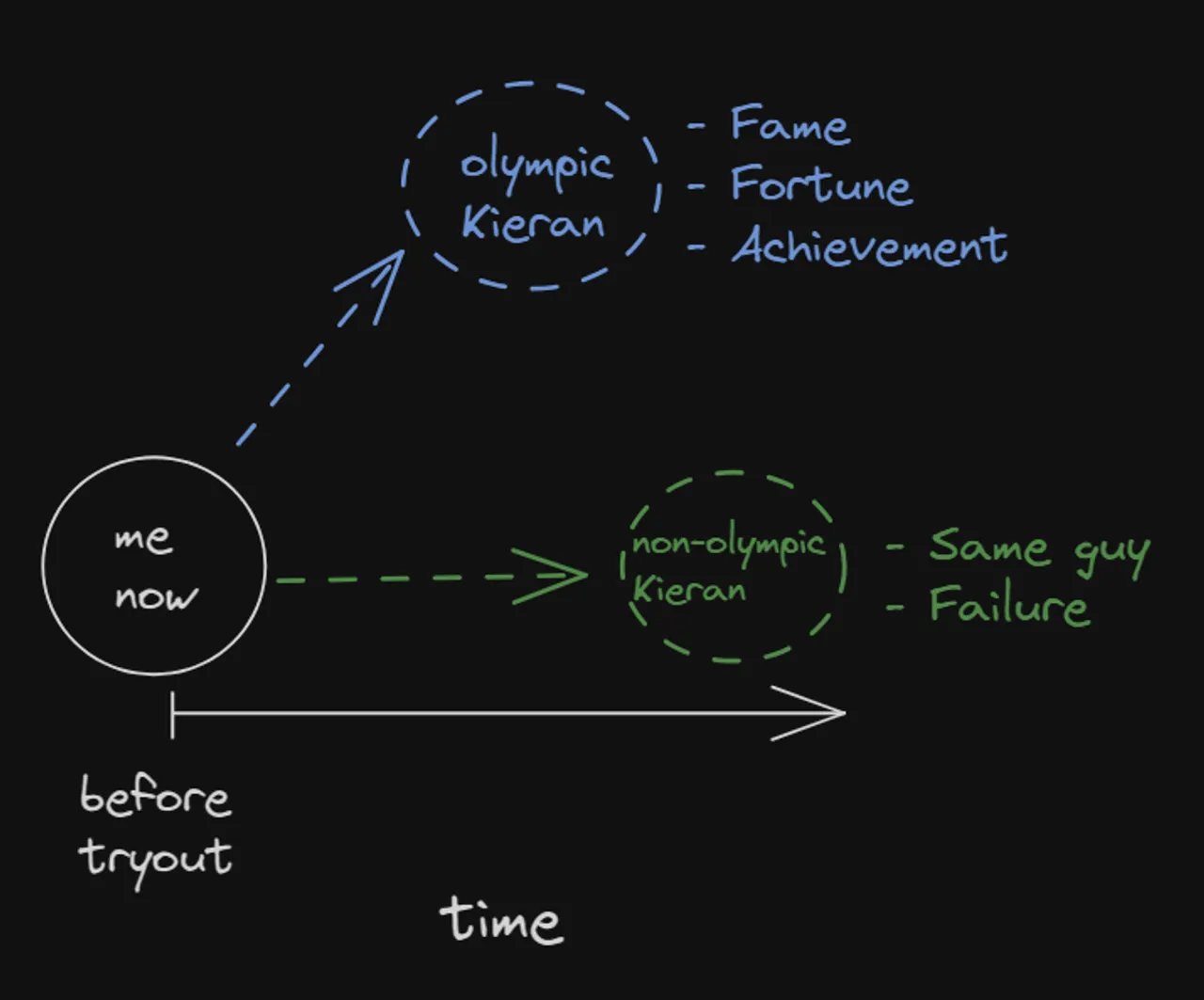

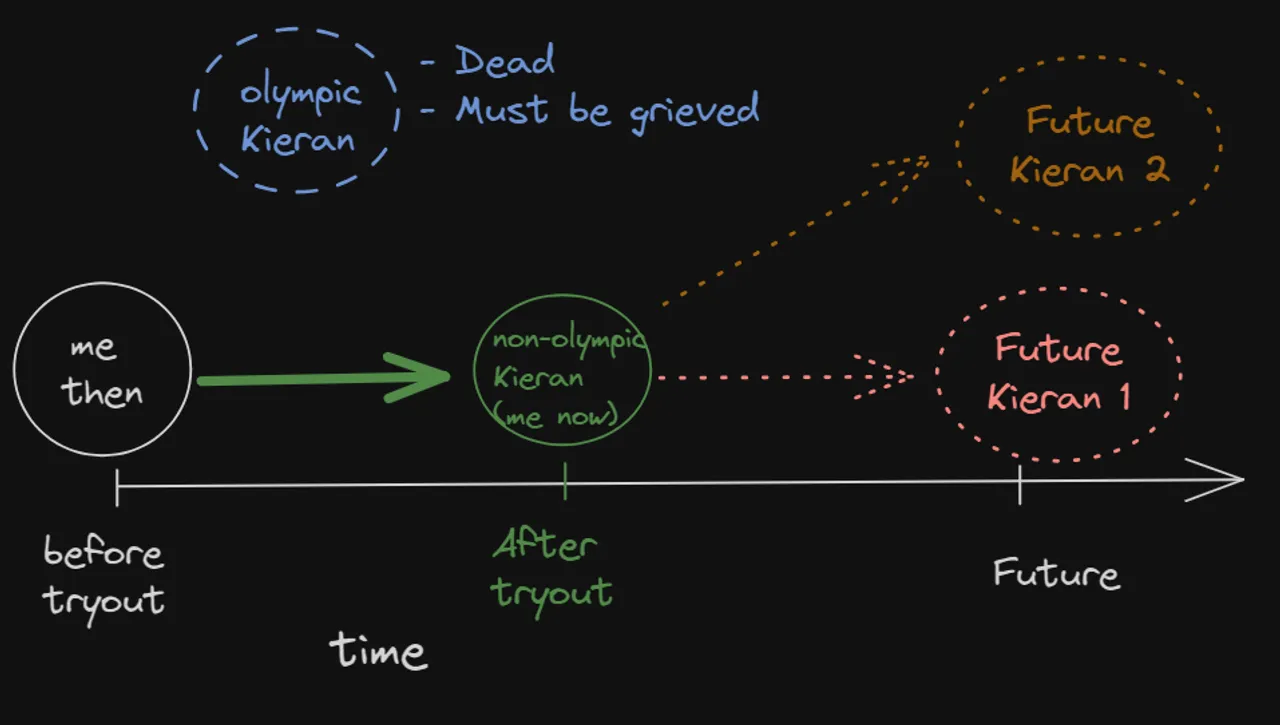

There are a few additional things to wrap up the idea of being close to yourself. The first that I would posit is, it’s quite common for “you” to be transient. People grow and change over time. A few years ago I read Kierkegaard’s Sickness Unto Death, and in it there’s a section where he talks about despair over possibility. Kierkegaard posits than when you fail to live up to an expectation, you are not necessarily upset about what happened, but grieving over the loss of the person you could have been if that thing didn’t happen. For example if you fail an Olympic tryout, it’s not that you failed that’s the problem, after all there’s always next year, you are upset about losing the possible version of yourself that is an Olympic athlete:

Possibilities before tryout

Actuality afterwards, with future possibilities

I think this model of despair can also be useful for understanding yourself, and helping actualize your possibilities. I argue there is not 1 self, but a current self that is an iteration in a long series of “selves”. These selves are always transient, and who you are does not always have to be set in stone. With this mental model there is obviously a difficulty in understanding yourself with an ever-changing situation.

Self-analysis

Even without the complexities of the Kierkegaard-inspired model understanding yourself is difficult. Who you are, and your underlying thought process is always opaque to you. Your reasons for doing things may seem like 1 explanation, but could be another thing entirely. Are you being selfish in making demands? or just setting healthy boundaries? Are you being greedy to charge more for your time? or just treating yourself with more of the respect you deserve? These questions and more will be coming up constantly.

Nietzsche in Thus Spoke Zarathustra talks often about his view of nature. His view is that nature is ever-changing. When a river erodes the banks that used to guide it, it simply flows in a new direction. Likewise I would argue that we should be in a constant state of flux and analysis. THe ever-changing target of understanding oneself is just that, ever-changing. At any given point you may have a relatively apt view of yourself, and that view may be completely incorrect in a few years.

Stone tablets

With this however there’s a concern for just always changing, and never forming your own self-identity. This comes up quite a bit in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. In the book the character Zarathustra takes note on the problem of the authorities of the day. The clergy, politicans and academics all seek to either eternally conserve, or impractically destroy the systems that maintain a society. There instead must be a situation where there is more of a solidified self-image, that can be open to changes when necessary. Nietzsche eludes to this through an allegory.

He talks about “the stone tables (or tablets in some translations)”. These tablets are an allegory to the ten commandments. He speaks to their importance, and then suggests their destruction 3. This is done because there should be a set of “set in stone” rules. These rules should be hard to eradicate, and should form the basis of your identity, however they should be adaptable. It’s just that the adaptability should be weighed seriously against the benefits of a stable platform. You should be able to change when you see good reason to, but the good reasons must actually be good. That game of whack-a-mole is probably in it for the rest of your life. However when making changes they should not be so transient that you have no concrete identity. You should instead continuously recreate stone tablets 4. When you have a change that will overturn your “core” beliefs you should tread carefully, but the things that are less important should be more transient.

Closeness to others

From the individual view we can now step into the complexities of our closeness to others. Not only is it complex to understand ourselves, but we often try to “see” ourselves through the eyes of another. We in kind also view the other person as an “other”. Fundamentally we have to do the same process as the individual, but with a few key differences.

The first being that our ideas of others are even more probablistic. We can’t observe peoples thought processes, only their actions. Therefore, we have even less information, and should be more willing to change our perspective on people (for better or worse). Second is that with others there’s an even further layer of complexity in managing your actual relationship to them. Your relationship can intrinsically change your perspective in that often people are not 1 person, they act differently depending on who they’re around.

Navigating relationships with others

With all this complexity I find that again the Kierkegaard model is helpful. When analyzing what someone is like, you need to know why you want to be around them. From there the question is whether that person maintains those important traits over time. Just like the Olympian from the previous example people will have different versions of themselves over time. At some point people can change so much that the person you started being friends with is for all intents and purposes dead. The question at that point is if you want to be around this new person or not. Funnily enough this is actually true in nature as well as a conjecture I’m proposing. Large portions of peoples cells are replaced constantly 5, so even your body itself is not set in stone, and neither are others.

Therefore, it’s worth it when dealing with people to try to treat them “as they are”, instead of “how they were”. There are cases when bringing up people’s past can be useful, but understand that no one owes anyone to stay the same forever. Likewise neither do you as an individual. If you want closeness, then it involves working with the “real” them not, not the potential “thems” in the future.

Closeness to the community

Lastly it’s worth mentioning a closeness to the community. This is a more sociological point than the previous psychological and existential ones. Everyone has a relationship to broader communities. This relationship effects what plays out in those communities, but also being part of these communities effects what plays out in ones life. Understanding a community (club, school, country etc.), is neigh impossible to do in full detail. Therefore we often have lower resolution “stereotypes” we use to understand these groups.

These can be “othering”, but they can also provide a “framework” to live your life by. People in religious groups for example will have a “way you’re supposed to live”. For example getting married and having kids as a method to “fit in”. While at first this seems to be counter to the point about Nietzsche made earlier (and it is), there is also a “euphoria” people have for belonging to a group. Feeling like you’re “in” a group can be a powerful effect, and sometimes it’s worth “playing ball” for the social acceptance. The main reason I brought this up however is because I would argue there is a sequence of importance with these relationships. Your closeness to a community I would argue is least important, then your relationship to others is more important, and your relationship to yourself is most important.

Preconceptions and positivity

Now that we’ve looked at these cases more closely a question still lingers. Is it as bleak as it seems? Well they all start from a set of preconceived value judgements:

- Closeness is an objective measure

- There is a “You” and “other” to understand

- Closeness is a “good” thing

For the first point I would posit that closeness is not an objective measure. The typical definition is something like understanding. The closer you are, the better you understand someone. However as we’ve seen there’s a limit to what that looks like. We cannot necessarily fully understand ourselves. Does that mean we can never be close to someone? No, there are 2 counter arguments to this point.

The first being that an unattainable definition is useless. So then the the key to this is the purpose in being close. The point of being close is to better understand someone in ways that feel meaningful. We don’t ask people for the chemical composition of their body in order to feel “close”, instead it’s an emotional closeness, or at it’s most clinical the capability to predict someone’s behavior’s. In both these cases we won’t get an absolute answer, but arguably part of being close in a colloquial sense addresses this problem. Most people would agree that being close to someone requires trust. If someone already knows the answer to what you will do then there’s no trust, it’s expectation. For trust there has to be a chance someone can do something else. Therefore ironically being close to someone requires some distance.

There is an interesting question about the second point. Is there actually one “you” and one “them” to get close to? As mentioned before there is arguably a transience in the understanding of oneself, and others. Arguably your understanding of others is their “social self”, that they let others see. Likewise others understand your “social self”. So in any interaction with one other person there is your self-perception, your perception of their social self, their perception of your social self, their perception of themselves. Likewise many people have a social malleability to how they represent themselves. Therefore, it’s hard to actually fully define what the “real” self is when you’re interacting with others.

Lastly there’s an assumption socially that closeness is something you want. Even trivially this isn’t necessarily the case. If there has ever been someone you don’t like, it’s unlikely you care to be close to them.

Wrap it up

This was a very long essay, however I think it’s worth highlighting some of the key points to reenforce them upon closing. We are othered from ourselves, and from other people. Those different manifestations have a similar, yet slightly different approach to navigate. While it may seem at first like the quote from the beginning is a negative one, it’s also worth keeping in mind more broadly why it was said. The quote exists because people want to be close. The fact that we cannot be perfectly close does not mean that we cannot be close to people. This topic is only important because of the fact that there are people worth being close to.

The mysteries of yourself and another person do also present an opportunity to get close. When dealing with others this also means you need to create a more “human” bond that is based on trust in your “reading” of them, rather than something directly measurable you can rely on. Also your own self, and understanding of others is transient. All of these things make it difficult to understand people, but it’s a hard and consistent problem worth trying. It can be a beautiful struggle to continue to understand people, and hopefully one that everyone tries their best at to continue to improve over the course of their lives.

Footnotes

-

Negative Bias: Why We’re Hardwired for Negativity (verywellmind.com) ↩

-

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/social-influence/202110/7-things-we-often-get-wrong-about-other-people#:~:text=1.-,People,-like%20us%20more ↩

-

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm#:~:text=BESIDE%20the%20bad%20conscience%20hath%20hitherto%20grown%20all%20KNOWLEDGE!%20Break%20up%2C%20break%20up%2C%20ye%20discerning%20ones%2C%20the%20old%20tables! ↩

-

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1998/1998-h/1998-h.htm#:~:text=Therefore%2C%20O%20my%20brethren%2C%20a%20NEW%20NOBILITY%20is%20needed%2C%20which%20shall%20be%20the%20adversary%20of%20all%20populace%20and%20potentate%20rule%2C%20and%20shall%20inscribe%20anew%20the%20word%20%E2%80%9Cnoble%E2%80%9D%20on%20new%20tables. ↩

-

Does Your Body Really Replace Itself Every Seven Years? | HowStuffWorks ↩